Introduction

Since 2015, I have been working on a combination research project and public resource: the LGBTQ Game Archive.1 This project seeks to document all recorded lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) content in digital (and occasionally analog) games and currently covers the 1980s to the present. In part, this project was driven by the fact that even as queer game studies grows as an area of research, there is a persistent assumption that queer games are somehow new.2 The project began with a 2007 spreadsheet I made of games with LGBTQ content. This was just step one in a project where I interviewed people who worked in the games industry and games journalism about the reasons there was seemingly little LGBTQ content in games compared to other media.3 In total there were fifty-six games on that list, a fact that I documented entirely because a reviewer commented that I needed to demonstrate there was little LGBTQ content in games. In what felt like a snarky response, I added a footnote explaining this tangential data set. As my work continued on the industry and audience interview route, I mostly set the spreadsheet aside. I always assumed someone else would do the long historical look at LGBTQ content in videos games.

Fast forward to 2015 and that history had not been written. I was a tenure-track faculty member with a book out and an anthology on the way, a large multiyear grant project wrapping up, and a tenure and promotion—(and self-) driven need to start a new Big Project. Adding to that, I had an interested undergraduate, a research assistant assigned to me for the semester, a sabbatical coming up, and news of a five-year funding stream that could help get the project going. And thus, the LGBTQ game archive was born. The master list quickly grew from fifty-six to 151 to now over 1,200 games, only a fraction of which are completely researched at this stage. Each game takes from five to eighty hours to research and involves pulling together game wikis, walk-throughs, reviews, screenshots, videos, academic analyses, news coverage, blog posts, and when possible or necessary actual game play. It is a project that will never be fully complete, but that is simply inevitable given that historical records are always incomplete, and the exponential increase in game and game-like objects produced with LGBTQ content will, I hope, continue well beyond my own career.

What I enjoy about the work of the LGBTQ game archive is the piecing together of knowledge across sources, sites, countries, and so on. Doing LGBTQ game history requires always working with incomplete knowledge of the entire space, feeling my way through (practically and affectively) available records and anecdotes—a historical orientation akin to Laine Nooney’s method of “media speleology,” which she describes as a “phenomenologically imprecise encounter … [relying] on non-continuity and the inability to apprehend the historical field in its wholeness.”4 It is an act of discovery and puzzle solving but also one of community service. And yet I cannot say that this process is simply one of pleasure. The work is hard and often involves swimming in original materials that are deeply offensive as often as they are enjoyable. As a qualitative researcher trained primarily in ethnographic and textual analysis methods, with only limited training in archival research, I am used to reflecting on my relationship to human participants much more than historical documents. In the interest of scholarly transparency, then, I would like to reflect on the spectrum of affects that come from attempting to document LGBTQ game history. In addition, however, although I have written or spoken quite a bit about the project already, there is one story about the project that I have only ever told to my friends.5 In this essay, I review an experience that pulled a project intentionally focused on a lost gaming past into the political present. More than just an anecdote, however, this example demonstrates that game history can be (perhaps should be) troubled by the present. Much has been written connecting alt-right movements to recent controversies in game and geek culture, but can we abandon easy chronologies to consider how these processes take shape over a longer historical trajectory and among members of marginalized communities as well?6

Serendipity

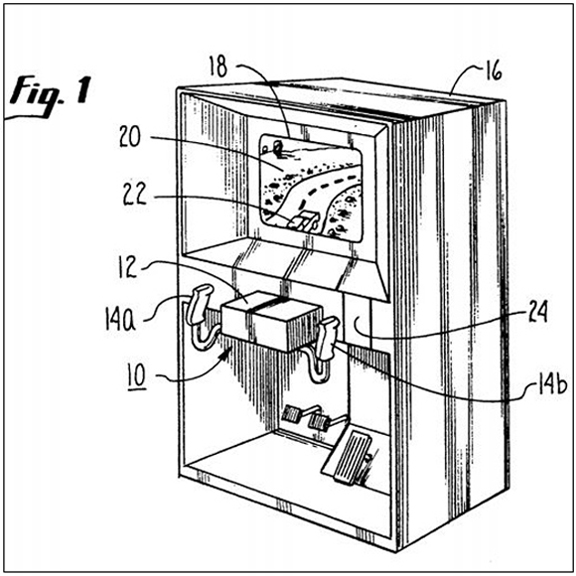

I am lucky that I have the resources and education at my disposal to recover a history that no one else has written about and the job security to make that process public with little worry about whether or not it counts in the tenure and promotion sense. And while all historians are aware that history is never truly complete, simply published, luck also informs the kind of research we can produce. For instance, when I made my initial list in 2007, the oldest games I found were Moonmist (Infocom, 1986), Mike Tyson’s Punch Out (Nintendo, 1987), Super Mario Bros. 2 (Nintendo, 1988), and Phantasy Star (Sega, 1989). When I returned to reconstruct my list in the fall of 2014, however, a new game had appeared that was different from the others: Caper in the Castro (C. M. Ralph, 1989). The Wikipedia list of games with LGBTQ content provided few details but included links to two articles by Luke Winkie.7 Both articles were published in the spring of 2014 just as the plans for my project were forming (fortuitous!). The game appeared to have been lost to history but in his June 2014 article, Winkie was able to interview C. M. Ralph and get enough detail to write up an entry for the LGBTQ Game Archive (see fig. 1).

Figure 1

As the LGBTQ Game Archive was getting off the ground, I did not have much time to research the game further than this. My project sought to document hundreds of games, and so when I reached a digital dead end on any one game, I wrote the entry to reflect all of the information gathered and moved on to the next one. Once the project became public and I was able to recruit a rotation of research assistants to help write new entries, however, I was able to redirect my energies toward fleshing out entries on some of the older games. And I chose to do so for a few reasons. First, Alayna Cole’s project Queerly Represent Me went public the same month as the LGBTQ Game Archive (also fortuitous!), and as that team sought to focus on creating a larger and larger list, I felt it was a good use of my time to focus on the archival documentation of the games.8 Moreover, as the list had grown and as I had begun various analysis projects, it became clear that there were gaps in the historical records. For instance, I noticed that there appeared to be no games at all that dealt with the HIV/AIDS crisis although that was the narrative of most gay and bisexual cismale (especially but not exclusively) media during the 1980s and 1990s in much of the world (though notably, given where major games of the time were produced, it was less of a widespread crisis in Japan).9 When I asked people if they were aware of games that dealt with HIV/AIDS from that era, inevitably folks responded: “There must have been.” But no one could name them. Similarly, everyone assumed there must be more independent LGBTQ games from the pre-2000s, but again few people could name them or direct me to information about them.

I decided that I could try to find out more about this era of game making by reaching out to C. M. Ralph to learn more. C. M. fortunately had a website with contact information, though unfortunately when I reached out, C. M. was in the middle of a big move after retiring from a manufacturing job in Silicon Valley. Most fortuitously, though, in the process of moving, C. M. had discovered the original diskettes for Caper in the Castro and Murder on Mainstreet (the straight version of the game made for a wider market). With the help of Andrew Borman at the Strong Museum of Play and Jason Scott at the Internet Archive, we were ultimately able to get the game online and playable (see fig. 2).10 My full interview with C. M. is published in the Rainbow Arcade catalog, produced as part of an exhibit at the Schwules Museum I cocurated and in which Caper in the Castro was on display as a playable game.11 During the interview, though, C. M. mentioned having been interviewed for the Washington Blade by a woman named Cynthia. Having not found many links to the LGBTQ press during the rest of the project, this was a bit of a light-bulb moment for me. Perhaps there were more games, especially from the 1990s and before, that had been documented in newspapers like the Washington Blade.12

Figure 2

Title screen from Caper in the Castro (C. M. Ralph, 1989). (Screencapture by Adrienne Shaw from SheepShaver emulation)

Excitement

Searching the Washington Blade archives, I was able to track down the interview C. M. had mentioned.13 This proved a little tricky as the digitized scans were not fully readable or searchable. I ended up going page by page through the issues from the year the game came out. And when I found it, I got so excited! (See fig. 3.) Written for the November 3, 1989, issue, Cynthia Yockey’s article reads like many 2010s articles about new games written by and for LGBTQ people: “Now, Why, you might ask (if you are from Mars, or do not have a personal computer), do Lesbians and Gays need a Lesbian/Gay-themed computer game? Well, why do you need Lesbian and Gay movies, or plays, or novels? BECAUSE THEY’RE AN EXPRESSION OF LESBIAN AND GAY LIVES, AND GAY PEOPLE DESERVE TO SEE THEIR LIVES EXPRESSED, THAT’S WHY!”

Figure 3

Headline from November 3, 1989, Washington Blade article by Cynthia Yockey about Caper in the Castro . (Screencapture by Adrienne Shaw from digitized copy of paper available from: https://www.washingtonblade.com/archives/)

The article also includes common feminist indictments of mainstream video game culture, arguing that Caper in the Castro means that a different future for games could be imagined: “Instead of games that reflect male values where the object is to gain power, defeat and destroy, there could be games written from women’s values where the goal could be to get the maximum number of people to like you … . There could even be consciousness-raising role-playing games like ‘Teen Pregnancy’ or ‘Patriarchy,’ where each player is required to alternate between characters of different genders and sexual orientations.” Here in 1989 we see the seeds of the prosocial and communication-oriented gaming that defined the girl games movement of the 1990s and perhaps even feminist commentary games like 2010’s Hey Baby.14 In addition, the article mentions that the game was created with HyperCard, a program that the author admits no one was fully sure what it was though it was largely sold as a visual database program for businesses. Thus, long before designers utilized the affordances of the hypertext tool Twine to make games without programming knowledge, Ralph had appropriated HyperCard for a puzzle-based narrative.15

The article moves on to a summary of the game, as well as a note that as of that writing, Yockey and a fourteen-year-old boy were the only people C. M. knew of who had beaten the game. It ends mentioning that the game was released as “Charity ware,” where it could be downloaded, and that it “is also on sale as a Macintosh shareware disk at meetings of the Prink Triangle Computer Alliance, the new national Lesbian and Gay computer user group for owners of IBM-compatible or Macintosh computers and that is headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland.” Yockey’s bio, moreover, revealed that she was the founder of the group. I do not know if I can fully express how excited this conclusion made me. Somewhere out there, in the late 1980s, there was a group of gay and lesbian computer users who were sharing Caper in the Castro copies and may just have knowledge of more LGBTQ games from the era.

Digging into the Washington Blade archives more, I found a small story in the April 6, 1990, issue highlighting the group.16 It was founded in September 1989, met monthly in DC, and had “about 25 members” at the time. The article reveals that Caper in the Castro was also the impetus for starting the group, which was intended to be both a meeting place for computer-savvy gay and lesbian members as well as a resource for people who needed help navigating computer and online resources. One of their goals was also to “establish a library of Lesbian and Gay male computer games.” I could find little else about this organization, although their events and resources were listed in the Washington Blade until at least 1993 according to a search through their archives.17

Whiplash

Much as I had done for C. M. Ralph, I tried to track down Cynthia Yockey. And what I found was that this same Cynthia Yockey who had treated a game featuring a lesbian detective rescuing her drag queen friends as an obviously important and historical game in the 1980s, who had other articles from the era calling to account gay and lesbian community events that lacked wheelchair accessibility … had become a conservative Republican. And not just any conservative Republican, but someone who had built a personal brand around being “A Conservative Lesbian” (see fig. 4).18 Her blog details her political transformation, which began in 2008 with the candidacy of Barack Obama, as one where her research had led her from being a liberal Democrat and believer in global warming to a fiscal conservative who rejected the notion that climate change was primarily driven by humans. An interview on another conservative blog indicated that she was also part of a group who felt betrayed by what they described as the Barack Obama campaign’s sexist rhetoric against Hillary Clinton during the 2008 Democratic primaries. From 2008 to 2018 her blog increasingly focuses on what she calls the “transgender coup” and seeks subscribers and donations to support her forthcoming book: War in the Women’s Room: How to Get Men in Dresses Out of Women’s Spaces, Save Your Children from Confusion About Their Sex, and Undo the Transgender Coup.

Figure 4

Title from Cynthia Yockey’s 2008–present blog. (Screencapture by Adrienne Shaw)

Her blog and general online presence demonstrate a strong connection to alt-right outlets, including attending Brietbart parties (she was once photographed with Andrew Brietbart himself), appearing on Louder Crowder, and writing for conservative news sites. Yockey’s personal blog has not been updated since February 2018, although she maintains an active Twitter account and one recent Tweet demonstrates she cares about accessibility of public spaces. I first came across Yockey’s blog and book project in late 2017; however, in updating my research it appears she wrote for Dangerous in early 2018, a website owned and operated by Milo Yiannopoulos’s company Milo Inc.19 The company is also identified as the publisher of her book. A February 2018 post from Yockey’s Facebook page for the book, however, was seeking funds because “two friends had promised her work and money” to write her book full-time but as of January 2018 no longer could. Another post to her blog from a month earlier demonstrated that she hadn’t received $600 she was expecting and needed to fundraise to pay a past-due internet bill. The book link on the blog site is no longer functional, and though her Twitter account lists Dangerous as the publisher, given the recent decline and then implosion of Milo Inc. that became public news by April 2018, the future of the book seems uncertain.20

Thus, the excitement of finding a potentially very important node in LGBTQ digital game history quickly pulled me back to the political present. Yiannopoulos’s and Brietbart’s rise in mainstream popularity following a well-publicized fight over and campaign of harassment around increasing inclusivity in games, and the use of members of marginalized groups siding with conservative politics in that and many a political battle need not be revisited here.21 Games since 2014 have become a space where every discussion of inclusivity has become a lightning rod for debates about censorship and “catering to SJWs.” I would be lying if I did not say that some of the impetus for focusing on LGBTQ game history was an effort to take a break from all of that. I also am not wholly surprised at Yockey’s political transformation nor her anti-trans stance given that there is a long history of feminist movements rejecting transwomen’s inclusion in women’s spaces. Even in that original Caper in the Castro article, her critique of games generally relies upon binary and traditional gender norms.

History is not linear nor is political progress, and doing this type of research is always an opportunity to be reminded of those facts. But for context, going from tracking down the Washington Blade article C. M. mentioned in our interview to uncovering Yockey’s links to the alt-right occurred in the space of thirty minutes for me. That’s quite the roller coaster of researcher emotions. And what I have been calling archival whiplash took me a bit to process, and I find myself always telling the story in the order I do above to give the listener a sense of what I experienced (affectively) because that is the lesson here for me. We go into research with expectations, even when we try not to, and our processing of data also requires processing of our reactions to our data. Beyond that, however, this research moment exemplifies that historical work connects us to the present; we make sense of it through the present. I wonder how game scholars might move beyond linear and chronological connections between conservative backlash on calls for diversity in games and late-2010s broader political conflicts. We can see why alt-right movements have found an easy home in gaming, but it is illogical political trajectories I am interested in (avoiding accusations of hypocrisy toward gay conservative figures like Milo and Cynthia Yockey).22 How might queer game scholars account for the fact that not all LGBTQ people (particularly those who might reject the label queer) have the same politics? One way might be to pull apart our notions of what constitutes LGBTQ gaming communities, past and present, and resist the temptation to impose order on messy political realities.23

Conclusion

After Caper in the Castro was added to the Internet Archive, someone wrote to thank me for my part in the work, saying: “You were essentially a digital archaeologist and when I say archaeologist I mean Indiana Jones, not realistic kind—you recovered all of the treasure with all of the glamour!” Although queer digital archaeologist might be a fun Halloween costume, I also think that this work is much less glamorous than it appears on the surface (but hearing things like that definitely makes it all worthwhile!). Instead, it is a particular combination of luck, networks, persistence, and thinking about alternative ways to find the information I need to document a history that has largely been forgotten. The excitement of uncovering forgotten histories, finding links of connection between sources as well as between the then and the now, is part of what makes this work enjoyable. And yet, it is also that excitement that can produce moments of whiplash, where the findings that were bringing us joy, throw us directly back into the conflicts of the past and present.

Footnotes

1. ^ “LGBTQ Video Game Archive,” LGBTQ Video Game Archive, accessed October 11, 2019, https://lgbtqgamearchive.com/.

2. ^ Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw, eds., Queer Game Studies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); and Bonnie Ruberg and Amanda Phillips, “Not Gay as in Happy: Queer Resistance and Video Games (Introduction),” in “Queerness and Video Games,” ed. Bonnie Ruberg and Amanda Phillips, special issue, Game Studies 18, no. 3 (December 2018), http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/phillips_ruberg.

3. ^ Adrienne Shaw, “Putting the Gay in Games: Cultural Production and GLBT Content in Video Games,” Games and Culture 4, no. 3 (July 2009): 228–53, https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009339729.

4. ^ Laine Nooney, “A Pedestal, a Table, a Love Letter: Archaeologies of Gender in Videogame History,” Game Studies 13, no. 2 (December 2013), http://gamestudies.org/1302/articles/nooney.

5. ^ Adrienne Shaw, “What’s Next? The LGBTQ Video Game Archive,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34, no. 1 (January 2017): 88–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2016.1266683; Adrienne Shaw et al., “Counting Queerness in Games: Trends in LGBTQ Digital Game Representation, 1985‒2005,” International Journal of Communication 13 (March 2019): 26; and Adrienne Shaw and Elizaveta Friesem, “Where Is the Queerness in Games? Types of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Content in Digital Games,” International Journal of Communication 10 (July 2016): 13.

6. ^ Adrienne L. Massanari, “Rethinking Research Ethics, Power, and the Risk of Visibility in the Era of the ‘Alt-Right’ Gaze,” Social Media and Society 4, no. 2 (April 2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118768302; Bridget Blodgett and Anastasia Salter, “Ghostbusters Is For Boys: Understanding Geek Masculinity’s Role in the Alt-Right,” Communication, Culture and Critique 11, no. 1 (March 2018): 133–46, https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcx003; and Nooney, “A Pedestal, a Table, a Love Letter.”

7. ^ Luke Winkie, “From a Pink Dinosaur to ‘Gay Tony’: The Evolution of LGBT Video Game Characters,” Salon, April 18, 2014, https://www.salon.com/2014/04/18/from_a_pink_dinosaur_to_gay_tony_the_evolution_of_lgbt_video_game_characters/; and Luke Winkie, “A Q&A with the Designer of the First LGBT Computer Game,” pastemagazine.com, June 9, 2014, https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2014/06/caper-in-the-castro-interview.html.

8. ^ “Queerly Represent Me: QueerlyRepresent.Me,” accessed October 11, 2019, https://queerlyrepresent.me/.

9. ^ James W. Dearing, “Foreign Blood and Domestic Politics: The Issue of AIDS in Japan,” accessed October 11, 2019, https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft9b69p35n&chunk.id=d0e8851&toc.id=d0e8851&brand=ucpress.

10. ^ Adrienne Shaw, “Caper in the Castro,” LGBTQ Video Game Archive (blog), August 23, 2015, https://lgbtqgamearchive.com/2015/08/23/caper-in-the-castro/; and Andrew Borman, “Game Saves: Preserving the First LGBTQ Electronic Game,” September 7, 2018, https://www.museumofplay.org/blog/2018/09/game-saves-preserving-the-first-lgbtq-electronic-game.

11. ^ Adrienne Shaw, Sarah Rudolph, and Jan Schnorrenberg, Rainbow Arcade: Over 30 Years of Queer Video Game History (Berlin: Winterwork, 2019).

12. ^ “Washington Blade: Gay News, Politics, LGBT Rights,” accessed October 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonblade.com/.

13. ^ Cynthia Yockey, “Tracker McDyke Matches Wits with Dullagan Straightman,” Washington Blade, November 3, 1989.

14. ^ Carly A. Kocurek, Brenda Laurel: Pioneering Games for Girls (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017); Jessy Ohl and Aaron Duncan, “Taking Aim at Sexual Harassment: Feminized Performances of Hegemonic Masculinity in the First-Person Shooter Hey Baby,” in Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First Person Shooter Games, ed. Gerald A. Voorhees, Joshua Call, and Katie Whitlock (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 319–39.

15. ^ Alison Harvey, “Twine’s Revolution: Democratization, Depoliticization, and the Queering of Game Design,” GAME: The Italian Journal of Game Studies 3 (2014), http://www.gamejournal.it/3_harvey/#.U8xCbYBdV8D.

16. ^ Chris Musser, “Out in Numbers: Pink Triangle Computer Alliance,” Washington Blade, April 6, 1990.

17. ^ Thanks to Avery Dame, founder of the Queer Digital History Project (http://queerdigital.com/), for confirming the group does not seem to be documented elsewhere.

18. ^ I purposely do not link to Yockey’s blog or the alt-right websites she is featured on so as not to contribute to their web traffic. Given the instability of their financial backing (see note 19 below), these links are also not certain to be stable in the long term.

19. ^ While doing research for this article, I learned that Yiannopoulos sold the website due to continued financial setbacks. As a result, all content became unavailable and I could not reconfirm the dates Yockey wrote for them. “Milo Yiannopoulos’ Website Dangerous.Com Was Sold,” Daily Dot, October 13, 2019, https://www.dailydot.com/layer8/milo-yiannopoulos-sold-website-dangerous/.

20. ^ Ben Schreckinger, “Yiannopoulos’ Business Implodes after Death of Crypto-Billionaire,” Politico, April 27, 2018, https://politi.co/2r3qx39.

21. ^ Kishonna L. Gray, Bertan Buyukozturk, and Zachary G. Hill, “Blurring the Boundaries: Using Gamergate to Examine ‘Real’ and Symbolic Violence against Women in Contemporary Gaming Culture,” Sociology Compass 11, no. 3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12458; Torill Elvira Mortensen, “Anger, Fear, and Games: The Long Event of #GamerGate,” Games and Culture 13, no. 8 (December 2018): 787–806, https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016640408; and Jean Burgess and Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández, “Mapping Sociocultural Controversies across Digital Media Platforms: One Week of #gamergate on Twitter, YouTube, and Tumblr,” Communication Research and Practice 2, no. 1 (January 2016): 79–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2016.1155338.

22. ^ Megan Condis, “Opinion: From Fortnite to Alt-Right,” New York Times, March 27, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/27/opinion/gaming-new-zealand-shooter.html.

23. ^ A related but tangential point is that the involuntarily celibate community was created by a queer woman, though it is now primarily associated with toxic geek masculinity. “#120 INVCEL: Reply All,” Gimlet, accessed November 1, 2019, https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/76h59o.

Headline of June 9, 2014, Paste article in which Luke Winkie interviews C. M. Ralph, creator of Caper in the Castro . (Screencapture by Adrienne Shaw from https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2014/06/caper-in-the-castro-interview.html)