In 1918, a bloody civil war was fought in Finland. The conflict was between the Red Guards, the paramilitary forces of the labor movement, and the German-allied White Guards, which consisted of landowners and those in the middle- and upper classes. The war had deep roots in the social inequality of predominantly agrarian Finland, which had experienced rapid population growth in the period leading up to the war. Almost forty thousand people died in the Finnish Civil War, but of those only about ten thousand deaths were a direct result of the fighting. The rest of the victims were either executed without a trial or died in concentration camps after the war had already ended. The war thus caused trauma that affected several generations. Finland, for a long time, was a country torn apart by war.

In 1918, the same year as the civil war was fought, three games dealing with it were published. All three games reflected the time of their publishing, but they all had a different focus, both on the level of what parts of the conflict they represented, but also in how they did it—by what rules and abstractions. A modern reader might easily be shocked that games were published so close to these traumatic events. One of the games, Helsingin valloitus (The Conquest of Helsinki, 1918), was even marketed as a “new fun game” in the press.1 This feels inexplicably brutal and thoughtless to us: How could games have been made of such terrible circumstances and marketed in this way?

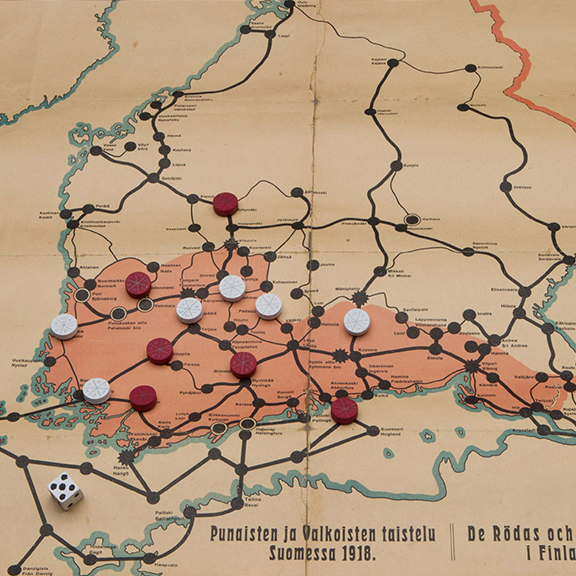

Figure 1

In this Materials piece, I will look in more detail at one of the three published civil-war games, Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 (The Battle of the Reds and the Whites in Finland 1918, hereafter P&V), which was distributed by Juusela & Levänen in 1918 just in time for the Christmas market (see fig. 1).2 Little known outside of Finland, it has attracted some interest among Finnish academics. Johanna Yrjölä has written about P&V in her master’s thesis, “Sisällissota pelilaudoilla” (Civil war on game boards) providing a close reading of the game, its contemporaries, and later civil war–themed games from a historiographic viewpoint.3 Jaakko Suominen has made a historical analysis of the game as part of a larger monograph on Finnish game history.4 In Annakaisa Kultima and Jouni Peltokangas’s The Praised, the Loved, the Deplored, the Forgotten, an interview with project manager Kimmo Antila details how P&V ended up in the Tampere 1918 civil-war exhibition in Museum Centre Vapriikki.5

I am interested in examining why this game was published in the year of the civil war. Why did P&V deal with such a contemporary and traumatic topic? Who made the game and why? Also, I will consider its relationship to other war-themed games of its time. As a game about current events, P&V necessarily combines elements of real-world representation with the abstraction of game rules. Existing research has looked at its representation of the war, but I am interested in the games as a system of rules, aiming to understand the nuances of the rules through play. What kind of war game is P&V and how does it relate to the history of hobbyist war games in general?

Finnish commercial board-game publishing goes back to 1862, when the bilingual Huvi-matka Avasaksaan (Pleasure Trip to Avasaksa) was put out by G. W. Edlund.6 Designed by female artist Hilda Olson, it was explicitly produced as a children’s game and as a tool for learning more about the Grand Duchy of Finland, then an autonomous part of the Russian Empire and the forerunner of modern Finland. Its rules are those of a simple race game where players work their way around various regions of Finland, but thematically it is fixated on contemporary events. For example, Huvi-matka Avasaksaan deals with the Finnish mark, the currency of Finland that had been introduced just a couple of years earlier in 1860. The first Finnish railway line from Helsinki to Hämeenlinna, which opened in January 1862, is also covered, as is steamboat travel, coffee, and other subjects that had recently been introduced into Finnish society when Huvi-matka Avasaksaan was published.

Figure 2

The Huvi-matka Avasaksaan (Pleasure Trip to Avasaksa) game board features depictions of iconic Finnish locations by artist Hilda Olson. Several of the depictions were the first images of those places ever reproduced.

Historians Henna Ylänen and Jaakko Suominen have written about this tendency of old board games to deal with contemporary events, labeling these types of games as “news games.”7 Other examples include games like Nordenskiöldin koillis-väylä (The Northeast Passage of Nordenskiöld, 1879), which dealt with the ongoing journey of Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, a Finnish Swedish explorer, on his way around Asia.8 While the first leg of the journey is a documentary account of Nordenskiöld’s travels in the Arctic Ocean, apparently based on letters sent to Finland from the Arctic Ocean in the winter of 1878–79, later events in the game are entirely fictional. Imagined events such as a marriage with a Javanese princess are featured alongside documentary drawings and accounts of the journey.

War has been a topic of games since at least the development of chess, but a striking number of news games also dealt with contemporary conflicts. In the Finnish context, most wars that Russia was involved in were featured in games published in Finland. The oldest known Finnish war game, Risti ja Puolikuu (Cross and Crescent, 1897), addresses the Greco-Turkish War of 1897; it uses checkers-style rules with game pieces advancing like checker pieces and progressing from man to king.9 The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5 was the topic of two games published in Finland at the time. Urhoollinen Port Artur (Valiant Port Arthur, 1904) represents the Russian side as “valiant,” whereas Japanilainen Sotapeli (Japanese War Game, 1906), published two years later, shows the Russian forces in a much more critical light, reflecting the changes in popular opinion toward Russian rule and Russification.10

Figure 3

Urhoollinen Port Artur (Valiant Port Arthur) was released with rules in Finnish, Swedish, and Russian. Unlike later games, it depicts the Russian war effort in a favorable light.

While earlier games were explicitly marketed to children, war games such as Risti ja Puolikuu, Urhoollinen Port Arthur, and Japanilainen Sotapeli seem to envision a different audience. The intended audience is rarely spelled out, but some later games explicitly mention that they are meant for both “young and old” (e.g., Maailmansota [The World War, 1914] and Suomen vapaussota [Finnish War of Independence, 1918]).11 Perhaps other games were also meant for an adult audience. One reason for this might have been the imposing boards themselves. The lithographic printing process invented in the late eighteenth century made striking full-color boards possible. While early games such as Huvi-matka Avasaksaan are black and white, colors gradually crept into games, which strikingly contrasted with other media of the time. Newspapers seldom had any pictures at all before the 1920s, and even then, they were grainy black-and-white affairs. Perhaps it would make sense to think of board games as a form of multimedia news that complemented text-based news distributed in newspapers?

As the defining event of the early 1900s, the First World War inspired an influx of games, not only in Finland but throughout the world. The website Board Game Geek features thirty-three games with a World War I theme published between 1914 and 1918, while the German-language study on war and games, Agon und Ares, features eighteen war-game entries dealing with World War I.12 These games range from quartet card games featuring soldiers, such as Weltkrieg-Quartett (World War Quartet, 1915),13 to games like Hurra! Mit Handgranaten vor (Hurray! Approach with Hand Grenades, 1915), in which players aim to throw scalable hand grenades at the enemy board by manipulating a marionette figure of a soldier.14

While war seemed to bring about innovative game mechanics, most published war games were still variants of well-known abstract games such as chess or checkers, or various kinds of race games. For example, Balkan sotapeli (The Balkan War Game, 1914) deals with the pre-WWI events in the Balkans during the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 and utilizes different modes of movement and speeds for infantry, artillery, and cavalry.15 The game is asymmetrical, as Turkey starts the game with much larger forces than Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro. The rules do not specify how many players are needed, but all countries have individual movement turns, with Turkey getting to move after each of the allies’ moves.

Not all games published during the war deal directly with military conflict. Seikkailumatka kotiin 1914 (Adventure Journey Home 1914, 1914) is a race game dealing with the so-called adventure of returning home to Helsinki from “Buda-Pest.”16 No game board has survived, but by reading the rules, one gets the impression that although the game does not directly simulate the military side of the war, the tone of the journey is one of hurry and even panic. Still, amid the chaos, the player clearly has the role of a tourist. For example, the rule booklet states that at Reims players need to stop to “enjoy the cathedral sights,” even if bombs and bullets “are flying all around.”17

Figure 4

The envelope in which Seikkailumatka kotiin 1918 (Adventure Journey Home 1918) was sold omits the first part of the title (“adventure”), instead printing Matka kotiin 1918 .

Other games seemed to look beyond the war. Suominen mentions a game called Rauhan peli (The Game of Peace, 1918), which was advertised in early January 1918, before the civil war started.18 No copies have survived, but apparently Rauhan peli was a card game dealing with hopes for the end of World War I. The rules of Maailmansota (The World War) have not survived either, but the cover of the game envelope states that it is a “party game for young and old.”19 The game board and counters suggest that Maailmansota was some kind of abstract simulation of military events.

Other games were more detailed. The rules of Maailmansota läntisellä sotanäyttämöllä (The World War in the Western Theater, 1914) have survived and detail the events of the Western Front in 1914.20 The game utilizes a system of hidden troop placement in the style of the French game L'Attaque (1909) designed by Hermance Edan, where combat results are determined by the rank hierarchy of the pieces engaged in battle.21 Troops in Maailmansota läntisellä sotanäyttämöllä include infantry, cavalry, and artillery units of various sizes, airships and mines, but also different naval units with their own hierarchy. It is the first known example of a Finnish game sold in a game box, and it is also the first recorded Finnish game with an expansion pack, Maailmansota itäisellä sotanäyttämöllä (The World War in the Eastern Theater, 1914).22 The expansion pack is not a full game and cannot be played on its own since it only includes a new game board depicting the Eastern Front of the war and requires counters from the earlier release.

Figure 5

Maailmansota itäisellä sotanäyttämöllä (The World War in the Eastern Theater) depicts the Eastern Front of World War I. It is not a full game, only including a game board on which the original counters and rules from Maailmansota läntisellä sotanäyttämöllä (The World War in the Western Theater) are used.

The next war games published in Finland dealt with the Finnish Civil War and were released in 1918. In the introduction to its rules, Suomen vapaussota (Finnish War of Independence, 1918) comes across as a glaringly pro-White game that vilifies the Reds and blames them for the war.23 The Reds are portrayed as a “misinformed crowd” that has “rebelled against the legitimate government” with the help of Russia, Finland’s “hundred year oppressor.”24 The introduction stresses that the White player must ensure that “Finland keeps its freedom or ends up in even greater tyranny.”25 Despite its White-aligned rhetoric, both sides of the game have similar forces and an equal chance at winning. Suomen vapaussota uses _L’Attaque–_type gameplay, with artillery units of various sizes, machine guns, recon troops, ski troops, cavalry, and infantry making up the troops. In addition, it features special rules for cutting railway lines or capturing enemy artillery pieces.

Unlike other board games discussed in this article, the race game Helsingin valtaus (Conquest of Helsinki, 1918) was published in a Christmas magazine.26 Also unlike most other games from the time its designer and artist are known. The game featured artwork by a famous Finnish artist and children’s book illustrator Rudolf Koivu. The text in the game is by author of children’s books and science fiction stories Arvid Lydecken and depicts the conquest of Helsinki by German troops in April 1918. Suominen sees the game as part of the conservative ideology of the magazine in which it was published, Pääskysen joulukontti (The Swallow’s Christmas Knapsack).27 Players are expected to identify with the winning White side and relive events tied to the war through it.

Figure 6

Suomen vapaussota (Finnish War of Independence) depicts the Finnish Civil War utilizing L’Attaque –type gameplay instead of the more nuanced approach of Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 .

Based on this brief historical account, games dealing with contemporary conflicts were nothing peculiar at the time. As noted, the authors of games were seldom known, and P&V is no exception. This makes it difficult to understand the motivations behind publishing games dealing with conflict, but in some cases information about the publisher might help. P&V was released by Juusela & Levänen, a company founded by Toivo Eemil Juusela and Juli Levänen in 1916 at the latest. In addition to games, Juusela & Levänen published postcards and children’s books, and the founders also had other businesses, including lottery organization and business-machine importing. After the war the company specialized in postcards dealing with the civil war from the winning White side, and most commentators have seen it as aligned with the Whites and their interests.28

Like most other games of its time, P&V was sold in an envelope. Based on surviving copies, the envelope contained a rules booklet, a printed game board, and a set of cardboard counters. Dice were not included, which was the default at the time. Three copies of the game are known. The copy in the collections of the National Library includes the envelope packaging but lacks the counters, whereas only the one in Satakunta Museum has the counters but does not have the envelope. The copy in the collections of Tampere Historical Museums includes the envelope but lacks rules and counters. The Tampere Historical Museums’ copy is on display in the Finnish Museum of Games and features replica counters based on the ones in Satakunta Museum.29

Figure 7

Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 was sold in an envelope containing rules, folded-up game board, and counters.

The 65 cm wide and 63 cm long game board is printed in three colors. It depicts Southern Finland plus parts of Germany and Russia and shows major roads and railroads as well as cities and municipalities. The game board uses black to denote roads, railroads, and cities; blue to show the borders of the Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga; and red to depict areas occupied by the Reds at the start of the game before major fighting began. The borders of Finland are shown, but the use of color makes it a bit unclear where Finland ends and Bolshevik Russia starts on the Karelian isthmus, perhaps intentionally.

Six key locations of the war are marked with black stars and a further six with white circles, and all the locations had special rules in the form of stanzas with four rhyming lines in the rules booklet. The events indicated with a black star are favorable to the White side, while events with white circles are favorable to the Red side. For example, the city of Tampere, a major industrial city and the site of most of the combat, was one of the key locations for Red troops; its four-verse rule says: “When the Whites gallantly march to Tampere / The Reds must make for a quick escape / (within three spaces or closer / all Red forces fall immediately).”30 The original Finnish rules are presented in rhyming couplets, while the Swedish version seems to be a free translation of the (perhaps original) Finnish text.

Figure 8

Rules for specific locations in the Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 rules booklet are written in rhymed couplets.

Setting game rules in rhyming poetry was nothing new. The tradition of rhyming game rules in Finnish games goes back to Huvi-matka Avasaksaan, and it was common after that as well. Rules as poetry pose problems, though. Some stanzas are quite unclear about what they mean for movement and other game actions. For example, in Pahankosken silta (The Bridge over Pahankoski), it is not completely clear if White troops entering or passing the location should be affected. This tension between game rules as simulation versus the representation of war events as poetry creates (to modern players) a curious combination of hardcore conflict simulation and poetic interpretation.

Compared to other war games from Finland, the rules of P&V are more intricate. Unlike L’Attaque–type games with multiple military units, P&V has only two types of units, artillery and infantry, but the game board and the rules dealing with their movement are more complex than in games that have more units. Both sides have six units, comprised of one to six thousand men, as specified by a roll of a normal six-sided die. Strangely, the rules do not indicate how many of the troops are artillery and how many are infantry, but based on the game’s counters, we might come up with an interpretation. By examining the actual unit counters preserved in the Satakunta Museum, we see that the counters were printed on double-sided cardboard. One side depicts an infantry unit and the other an artillery unit. It seems that the player would decide how to deploy their troops, which would also explain why the rules do not further specify the number of infantry and artillery units a player might have.

Figure 9

Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 as it was on display in the Tampere 1918 civil war exhibition. The counters and dice are not original. (Courtesy of Tampere Historical Museums)

Both unit types move with the throw of the dice, but artillery can only move along railroads, while infantry can also move via roads. Combat resolution is abstract and dependent on dice. The rules speak of toppling over (kaataa) enemy forces when an active player unit encounters an enemy unit, with artillery pieces toppling over one more unit(s) than their die roll allows for. As is common for the times, the rules are very short and devoid of detail. All game rules fit into the six pages of the rules booklet, half of which is dedicated to the rhyming stanzas in effect in the special locations. The rules contain no examples of play, and they can be interpreted in various ways, meaning that a complete understanding of the rules would probably require actual play. Games can be understood without playing them, but when they are playable, playing gives an added nuance to their interpretation. Through play different interpretations can be tested out and evaluated. The intricacies of the game might be difficult to discern without actual play experience, and it is only through play that potential biases can be seen. Still, while poorly explained rules can be tested out and validated by play, we also need to be careful not to overinterpret games based on today’s play expectations. The cultural context related to playing games has changed since the early 1900s, and without primary sources, it is impossible to know what past play was like.

What especially sets P&V apart from its contemporaries is its neutrality. The game is surprisingly balanced and does not include historical revanchism, unlike Suomen vapaussota, for example. Only the following sentence in the P&V rules appears to blame the Reds: “The Reds always start the game,” which may allude to the Reds’ responsibility for the outbreak of the civil war.31 This is vastly different from the rhetoric used in Suomen vapaussota. The dedication to neutrality extends to the actual gameplay. While the setup of forces is asymmetrical, both sides start play with the same number of military units (although their strength is up to chance). This makes play interesting in the manner of an abstract strategy game but is not very historical. Troop numbers and quality differed greatly between the two sides of the war, with the Whites having many more career officers, for example.

P&V is by no means a modern simulation of war, but the rules lend it an interesting strategic and tactical element. Still, the scope and geopolitical clear-sightedness make it most fascinating. Unlike Suomen vapaussota, which deals with the Finnish Civil War as an isolated Finnish event, or Helsingin valtaus (Conquest of Helsinki), which depicts a single event in the war from the White side, P&V sees the war as part of a larger European conflict. This sets it apart from other contemporary accounts of the war, and even most historical analysis afterward. Until the 1990s, scholars rarely viewed the Finnish Civil War as part of the First World War, so P&V can be seen as a forerunner in understanding the civil war as part of a European or even global conflict. Based on this, we might hypothesize that the game was designed by someone familiar with military operations and conflict studies, perhaps someone associated with the military at the time.32

Board games dealing with contemporary events were widespread in 1918, and war had been and was still a common topic for them. Nonetheless, war games were tied to earlier traditions of simulating war in the vein of abstract strategy games like chess and checkers. In this context, P&V comes across as a surprisingly astute and intricate simulation of the Finnish Civil War as part of a global conflict, something different from other contemporary depictions of the war. While we do not know the designer and intended audience of P&V, we can presume that the designer was somehow militarily schooled. Based on evidence from other similar war games, P&V’s intended audience would have included both young and adult players, probably from a higher social stratum.

As a historical artifact, P&V might be difficult to fully understand without playing it. Gameplay instills a greater appreciation of a game’s complexity and the nuances of its rules. But play is never simple or uncomplicated; rather, it is based on a lot of tacit knowledge that a modern audience might not possess. The extent of this type of implicit knowledge and its importance for historical board games is difficult to assess, as modern readers might have difficulty understanding play conventions that historical players would have known. Still, actually playing historical artifacts might help in making sense of them, since play will highlight the absence of rules and might help determine ways that historical players would have navigated these gaps in the written rules.

Similarly, P&V and its rules are very much tied to the materiality of the game. The material components of P&V convey meanings and information about how the game should be understood and interpreted, and game components and their affordances might help to make sense of the gaps in the rules. If we want to understand historical board games, we also need to account for the tacit knowledge of their players as well as the materiality of the games themselves. If we can see beyond the game text toward such ephemeral meaning-making processes, the relationships among games, contemporary events, wars, and materiality will have more to offer to historians and game scholars alike.

Footnotes

1. ^ Most Finnish games at the time were bilingual or even trilingual, with rules in Finnish and Swedish and in some cases even Russian and German. In this article, I will be using the Finnish names of the games. Helsingin valtaus (Conquest of Helsinki) was published in Pääskysen joulukontti (Otava, 1918) and was marketed as a “uusi hauska peli” (a “new fun game”) in Uusi Suometar, no. 264 (December 9, 1918): 5.

2. ^ Punaisten ja Valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 (Juusela & Levänen Oy Kirjapaino, 1918).

3. ^ Johanna Yrjölä, Sisällissota pelilaudoilla: Suomen sisällissodan muistokulttuuri lautapeleissä 1918 ja 2018 (University of Helsinki, 2020), http://hdl.handle.net/10138/316415.

4. ^ Jaakko Suominen, Pajatsosta pöytätennikseen (Gaudeamus, 2023).

5. ^ Annakaisa Kultima and Jouni Peltokangas, The Praised, the Loved, the Deplored, the Forgotten: A View into the Wide History of Finnish Games (Tampereen kaupunki, 2019), https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/120127.

6. ^ Like most Finnish games from this time, the game is bilingual, but only the Swedish name, Lustfärd till Avasaksa, is featured on the cover. I will use the Finnish name in this article. Huvi-matka Avasaksaan (G. W. Edlund, 1862), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/130023.

7. ^ Henna Ylänen, “Kansakunta pelissä: Nationalismi ja konfliktit 1900-luvun alun suomalaisissa lautapeleissä,” Ennen ja nyt, no. 1 (2017), https://journal.fi/ennenjanyt/article/view/108787/63784; and Suominen, Pajatsosta pöytätennikseen, 149.

8. ^ _Nordenskiöldin koillis-_väylä (Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seuran kirjapaino, 1879), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/149552.

9. ^ Risti ja Puolikuu (Aktiebolaget F. Tilgmanns Bok-o. Stentryckeri, 1897), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/123549.

10. ^ Urhoollinen Port Artur (Aktiebolaget F. Tillmanns Bok-o. Stentryckeri, 1904), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/123550; and Japanilainen sotapeli (Lilius & Hertzberg osakeyhtiö and K. P. Winter, 1906), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/157035.

11. ^ Maailmansota (A. B. Gust, 1914), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/169581; and Suomen vapaussota (Kustannusliike Minerva, 1918), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/133927.

12. ^ Board Game Geek, https://boardgamegeek.com; and Ernst Strouhal, ed., Agon und Ares: Der krieg und die spiele (Campus-Verlag GmbH, 2016).

13. ^ Quartet card games, or quartets, are games with a dedicated deck and where the aim is for players to collect four cards in a series. The most well-known quartet game is Happy Families.

14. ^ Weltkrieg-Quartett (1915); and Hurra! Mit Handgranaten vor (1915).

15. ^ Balkan sotapeli (Kähler Martin, 1914), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/152852.

16. ^ Seikkailumatka kotiin 1914 (Werner Söderström osakeyhtiö, 1914), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/169742.

17. ^ The lines rhyme in the original Finnish: “Vaikka täällä pommit kuulat / Räiskyy joka puolla, / Täytyy sinun ihaella / Tuomiokirkkoa tuolla.”

18. ^ Rauhan peli (Toivo Lepistö, 1918), mentioned in Suominen, Pajatsosta pöytätennikseen, 147–48.

19. ^ “Seurapeli nuorille ja vanhoille.”

20. ^ Maailmansota läntisellä sotanäyttämöllä (Öflund & Petterson, 1914), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/133655.

21. ^ L’Attaque (Hermance Edan, 1909).

22. ^ Maailmansota itäisellä sotanäyttämöllä ( Öflund & Petterson, 1914), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/155559.

23. ^ Suomen vapaussota (Kustannusliike Minerva, 1918), https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/133927.

24. ^ “Harhaanjohdetut joukot” / “nousseet kapinaan laillista hallitusta vastaan” / “maan satavuotinen sortaja.”

25. ^ “Hänestä riippuu, onko Suomi säilyttävä vapautensa, vai joutuva entistä suurempaan sortoon.”

26. ^ “Helsingin valtaus,” in Pääskysen joulukontti (Otava, 1918).

27. ^ Suominen, Pajatsosta pöytätennikseen, 160–61.

28. ^ Suominen includes an overview of Juusela & Levänen’s other business ventures (152–53).

29. ^ The Finnish Museum of Games is a cultural history museum in Tampere, operated by Tampere historical museums and supported by the Pelikonepeijoonit game collector group and the Game Research Lab of Tampere University. The museum deals with the history of Finnish video games and their analog counterparts, such as board games and tabletop role-playing games.

30. ^ The Swedish version seems to be a free translation of the (perhaps original) rhyming Finnish text: “Valkoiset kun Tampereelle marssii uljahasti, / punaisille lähtö tulee varsin joutuisasti, / (päässä kolmen siirtovälin taikka lähempänä / joka punajoukko kaatuu hetkenä nyt tänä).”

31. ^ “Punaiset alkavat aina pelin.”

32. ^ Historian Tuomas Hoppu makes the same case in a video interview produced by the Finnish Museum of Games: “Interview: Tuomas Hoppu and Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918,” November 1, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBHtlMxuhWA.

Finnish Museum of Games researchers playing a reproduction of Punaisten ja valkoisten taistelu Suomessa 1918 (The Battle of the Reds and the Whites in Finland 1918) in 2016. (Courtesy Saarni Säilynoja / Vapriikki Photo Archives)