Editor's Note

This translation was commissioned with funds raised during ROMchip’s 2024 fundraiser. One of our stretch goals for that campaign was to support the translation of historically significant game writing. We’re proud to publish "Between Mass Culture and Technological Improvisation: The History of Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animalin Post-Dictatorship Brazil" to fulfill that commitment. For more on our fundraising goals and initiatives, visit: https://donate.romchip.org/fundraising-mission.html

Content Advisory

This essay contains sexualized images and racist depictions and should be regarded as “Not Safe for Work” (NSFW). Readers should continue at their own discretion.

Introduction

In September 1997, just before Grand Theft Auto (GTA) triggered a wave of panic that would lead to its ban in Brazil, newsstands across the country were openly selling a games-enthusiast magazine accompanied by a CD-ROM with content potentially so offensive that it made GTA seem like a walk in the park. Pooling together their school lunch money (R$8.50, or about US$7 at the time), kids could take home a game filled with scenes of violence and nudity, images of penises, and sexist, homophobic, and transphobic jokes—all of which, unlike GTA, were dubbed in Brazilian Portuguese.

This was Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal (Casseta & Planeta: Animal Night), originally released in late 1995 by ATR Multimídia, a Rio de Janeiro–based studio whose portfolio is, in itself, somewhat surreal (fig. 1). Founded in 1990, ATR Multimídia released works ranging from digital encyclopedias and educational games for children to an interactive erotic CD-ROM—artifacts from a pre-internet world.

Figure 1

The product was ambitious by Brazilian standards, which did not have much of a formalized games industry at the time: according to the TXT file located in the root of the gameʼs CD-ROM, its production took over a year and involved more than thirty professionals. The company did all of this to create a point-and-click adventure featuring the Brazilian comedy group Casseta & Planeta, popularized by the eponymous show on Rede Globo, the largest broadcaster and media company in the country. Born from the fusion of a humor fanzine and a satirical tabloid, the TV show Casseta & Planeta was a sort of Brazilian Monty Python, betting on politically incorrect humor with jokes about ethnic groups, religions, minorities, politicians, and everyday situations—all of which was well tolerated in the post-dictatorship era of 1990s Brazil.

The magazine that put the game on newsstands was PC Multimídia (fig. 2). Published by Quark Editora, it began in October 1996 as a special edition of the Brazilian version of the US publication CD-ROM Today. The debut issue of PC Multimídia included a CD-ROM featuring only children’s games. By December 1996, it became independent from the American magazine, coexisting with it as a separate publication.

Figure 2

PC Multimídia magazine, containing two CD-ROMs: one with the game Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal (ATR Multimídia, 1995), prominently featured on the magazine cover, and another with the game Betrayal at Krondor (Dynamix, 1993) along with demo versions of other games, including children’s games (Courtesy of Leandro Matioli)

Eventually children’s content became just a highlight, with each issue of PC Multimídia coming packaged with applications, demos, and a complete game. Despite the potentially young audience, it was not uncommon for the magazine to release complete games aimed at a more mature audience. For example, in the same year as it released Casseta & Planeta, PC Multimídia released full versions of the mildly erotic comedy adventure games Leisure Suit Larry 5 and Leisure Suit Larry 6 in the July and November 1997 issues, respectively. In the same CD-ROMs, there were shareware programs, utilities, and infantis, or games aimed at children.

In Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal, you play as a male teenager who needs to cross the city to get to a sex party (fig. 3). Filled with offensive jokes, the game aims to mock everything and everyone, including the players themselves: during the installation process, a message jokingly warns that it is formatting the userʼs hard drive. The adventure takes the protagonist through numerous unusual situations, represented by depraved versions of classic games.

Figure 3

The player starts the game in the teen-aged protagonist’s bedroom. ( Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal [ATR Multimídia, 1995]) (Screenshot courtesy of André Campos)

A Tetris satire replaces the traditional blocks with representations of male genitalia of different ethnicities and sizes, associating the largest with Black men and the smallest with Asian men (fig. 4). At a carnival-style shooting booth, you must fire a phallic-shaped arrow at cis women in sensual poses while avoiding the signs featuring drag comedians. In the shooting minigame “Serial Killer,” you score points by hitting targets, such as J. F. Kennedy in his presidential convertible or an old lady with a cane. Others, like a Ku Klux Klan member who, when removing their pointed hood, is revealed to be a Black woman with an Afro hairstyle, deduct points from your score (fig. 5). Thereʼs a Pac-Man of little penises that takes place in a gay sauna, where you must eat others but not be eaten; a Wolfenstein-style shooting minigame with the same drag comedians as enemies (alongside floating breasts that shoot milk); and a Street Fighter clone set in a prison, where, if defeated, the protagonist is made to be the “wife” of their cellmate (fig. 6). From start to finish, Noite Animal exploits and reinforces stereotypes of gender, race, sexual orientation, and social class, employing humor that is sexist, xenophobic, and homophobic.

Figure 4

The Tetris -based minigame replaces the blocks with penises of different sizes and shapes, assigning the smaller ones to East Asian people and the larger ones to Black people ( Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal [ATR Multimídia, 1995]) (Screenshot courtesy of the author)

Figure 5

Among the moving targets in the “Serial Killer” minigame are a figure resembling Adolf Hitler, J. F. Kennedy in his presidential convertible, and a Ku Klux Klan member who, upon removing their pointed hood, is revealed to be a Black woman with an Afro hairstyle. ( Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal [ATR Multimídia, 1995]) (Screenshot courtesy of the author)

Figure 6

A Street Fighter 2 –inspired minigame is set in a prison cell. If the player loses the fight, they become the “wife” of the other inmates. ( Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal [ATR Multimídia, 1995]) (Screenshot courtesy of the author)

By all accounts, Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal is a game that deserves to be forgotten and abandoned in the trash bin of history. It represents no great technological achievement or pinnacle of game narrative and has nothing to offer as a design inspiration. So why talk about it?

To answer this question, we need to look at how Brazilian games captured the tensions of a country that had recently emerged from a dictatorship, transitioning from a closed and protected economy to an open, globalized, and neoliberal one, where local computing products, especially games, competed at a disadvantage. In other words, Noite Animal arose in an industry context where local software producers could only offer uniquely Brazilian material—in this case, some of the most popular, and provocative, figures from Brazilian television.

But the existence of Casseta & Planeta itself, as a television-show-cum-computer-game, is also a plot point in a twenty-one-year history of mass culture and popular expression under the censorship regime of a dictatorship. While Brazil has long been situated as a historical novelty of the Global South, its histories largely antecedent or collapsed into a broader history of the Latin America game industry, this article is one small effort to seriously consider the context of Brazilian game production. By exploring the long arc of the economic, technological, and cultural dynamics that converged into the existence of Noite Animal, we gain an expanded view of the historical factors that shaped the Brazilian game industry, as well as popular engagement with and exploration of mass culture more generally.

Mass Culture During the Dictatorship

To understand the existence of a game like Noite Animal, we first have to contend with this history of a different medium essential to constructing Brazilian mass culture: television.

By 1995, television was regarded as an essential household item by the Brazilian population, present in 81.04 percent of homes—outpacing refrigerators (74.8%), water filters (57.8%), and telephones (22.27%).1 While the 1990s marked a high point in television’s cultural and social influence, the medium had long shaped the country’s political landscape, as well as the daily lives and habits of its people—extending back to the advent of Brazil’s military dictatorship in the mid-1960s. Television’s media power, which also influenced the production of games and entertainment software during the rise of the personal computer in Brazil, was established during the military regime.

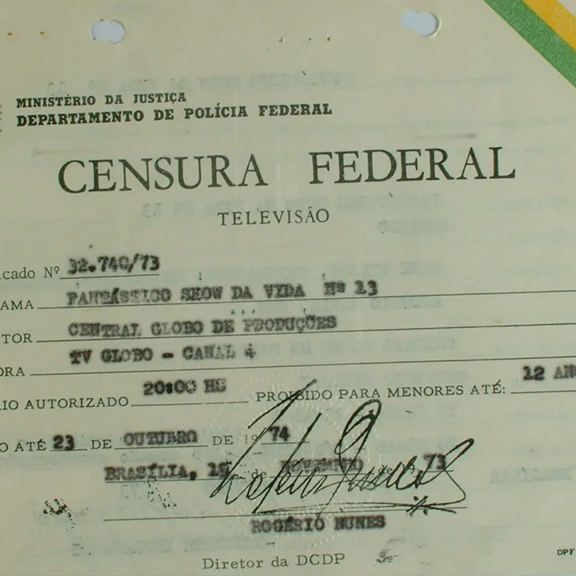

On April 1, 1964, João Goulart, who was democratically elected president of Brazil in 1961, was deposed through a military coup supported by the United States, under the pretext that the country was on the verge of communism and needed order restored. From that moment, the military regime closely monitored any public production, reproduction, and publication of literary, cultural, and media content. There was even a department in the Federal Police literally called the Public Entertainment Censorship Division, which evaluated everything shown in cinemas, radio, theater, television, and other media.2 Division censors removed anything they deemed inappropriate or counter to the military government. Before a show was aired, a static screen would display a document with the governmentʼs stamp of approval for the screening (fig. 7). The aim was to control the dissemination of any ideas that could threaten the established structure, promoting a vision aligned with the values and objectives of the government while repressing any criticism or expression deemed subversive.

Figure 7

During the dictatorship, before a TV show aired, a static screen would display a document with the government’s stamp of approval for the screening. In the image, Fantástico , a program on TV Globo, receives authorization for a broadcast starting at 8:00 p.m. (Image courtesy of Arquivo Nacional de Brasília)

Television played a crucial role during the military government, with Rede Globo, in particular, serving as a key ally by disseminating news favorable to the regime.3 Despite being a relatively new medium in Brazil at the time, it received substantial government investment.4 These efforts transformed television into a dominant mass-communication platform, widely regarded as a symbol of the nation’s purported progress—as well as a tool to influence and direct popular thought.5

Intriguingly, the focus on suppressing political dissent opened space within Brazilian entertainment television to pursue more scandalous or provocative content than one might expect—so long as the programming avoided political critique. One of the biggest TV personalities during Brazilʼs military period was Chacrinha, a flamboyant and iconic host known for his chaotic, carnival-like variety shows blending music, humor, and absurdity. His programs featured extravagant costumes, lively musical performances, playful interactions with the audience, and surreal giveaways of fruits and household items. One of its main attractions was the chacretes, dancers who played a central role, with skimpy clothing and provocative choreography, which over time added an increasingly sexual tone to the program (fig. 8). Chacrinha adopted humor that included double-entendre jokes, reinforcing sexist stereotypes.6 This style, although not entirely approved by censorship, was tolerated by the government as it was seen as a form of entertainment that diverted public attention from political or critical themes, aligning with the escapism promoted by the military dictatorship.

Figure 8

A 1978 photograph of the “chacretes” dancers, who added a sexual tone to Chacrinha’s shows. He was one of the most popular figures on Brazilian television in the 1970s and 1980s. (Image courtesy of Agência O Globo)

Accompanying the mainstreaming of television as a uniquely Brazilian mass medium and the normalization of sexualized moving-image content, the late 1960s also saw the emergence of pornochanchada in Brazil, a popular film genre that similarly blended comedy and sex (fig. 9). Pornochanchada, however, was often more implicitly subversive, reflecting behavioral shifts that came in the wake of the sexual revolution, marked by the popularization of the birth-control pill, urbanization, and the tensions introduced by the feminist movement.7

Figure 9

Mixing comedy and sex, pornochanchada was the most popular film genre in Brazilian cinema during the dictatorship. Poster of the film A Dama da Zona (1979) (Image courtesy of Cinemateca Brasileira)

Operating within the context of strict political censorship, filmmakers found ways to use everyday humor and spicy content to subvert political repression. While government censorship authorities imposed limits on what could be recorded for purposes of cinematic distribution—including explicit sex, full-frontal male nudity, or homosexual sex—pornochanchada utilized obscene and vulgar humor, as well as gender stereotypes, to address issues such as social inequality, workplace power dynamics, structural misogyny, racism, and political violence—though it often ended up promoting the very things it seemed to denounce.8 If Chacrinha embodied government-sanctioned escapism, sexuality, and provocation devoid of explicit politics, the pornochanchada used humor to politicize sex in a way that censors couldn’t quite stamp out.9 Furthermore, a government-mandated quota for the exhibition of national films, intended as economic- and cultural-development measures, further stimulated the proliferation of the genre.

Thus, while there was a strong climate of censorship in mass-culture production during the Brazilian dictatorship, film and television producers found a loophole with sexualized, often sexist, humor, which was largely tolerated by censorship authorities. As a result, this type of content became the norm in Brazilian mass culture.

By the 1980s, the production of pornochanchada began to wane due to the influx of foreign pornography films (including on VHS), the popularity of television, and the economic crisis in Brazil. Many directors, screenwriters, and actors who worked with pornochanchada migrated to television, bringing characteristic elements of the film genre, such as suggestive humor and sexual appeal, to popular television shows. The sexualized content already normalized in television by Chacrinha expanded, facilitated by the popularity of escapist entertainment, fueled by the dictatorship.10

Brazilʼs dictatorship came to an end in 1985, driven by a groundswell of popular demand for democracy—embodied by social movements like Diretas Já—coupled with deep economic crises and the unraveling of the military regimeʼs political grip. This heightened the feeling of freedom of expression on television, which—although still monitored by rating bodies—no longer dealt with the rigid censorship of the military regime. While television began to explore the freedom of opinion in democracy, it also increasingly stretched the limits of potentially offensive humor, sensationalist content, and sexually suggestive material, even in daytime shows, entering a phase of enormous permissibility compared to its American or European counterparts.

For example, by the 1990s, Sunday afternoon shows that Brazilian families watched during their lunches featured groups like É o Tchan, known for dancers in tiny shorts performing choreography that involved squatting with open legs over a bottle. Guguʼs Bathtub, a segment of the television show Domingo Legal, operated in a similar vein, where celebrities in swimsuits had to find slippery soaps in a large circular bathtub while voluptuous bikini models tried to stop them. And in the late 1990s, childrenʼs products were created based on the character Tiazinha, who sported black lingerie, a mask, and a sadomasochistic whip (fig. 10). She became famous for a segment on a TV quiz show where young men had to answer questions correctly; otherwise, she would punish them with hot wax.

Figure 10

The character Tiazinha, played by actress Suzana Alves, wore black lingerie, a mask, and carried a sadomasochistic whip. She waxed young men in a quiz segment on the TV show Programa H . In 1999, a children’s shoe line inspired by the character was launched, featuring a mask as an accessory. (Image courtesy of Carlos Ivan/Band)

It was in this setting that Casseta & Planeta—as sexist, homophobic, and racist as it was—became one of the most popular weekly humor shows on Brazilian TV. The broader historical context of Brazilian film, and especially television, helped shape a national popular culture that was, and continues to be, more permissive toward sexual and provocative content.11 In this setting, television, which reigned in Brazilian living rooms as the most powerful mass media, with a strong legacy from the dictatorship, began to share space with another type of screen: that of computers.

An Interrupted Industry

At the end of the 1970s, the military regime established the National Informatics Policy to reserve parts of the computing industry for local markets; this prevented the sale and importation of computers from multinational companies and encouraged local hardware manufacturing. Numerous social sectors supported the policy, including academics, industrialists, and businesspeople.

This measure gave rise to a Brazilian microcomputer industry and market in the first half of the 1980s, created from the reverse engineering of foreign machines, such as Microdigitalʼs TK90X, based on Sinclairʼs ZX Spectrum, and Sharpʼs HotBit, based on the Japanese MSX.12

Similarly, reverse engineering occurred in the consumer software market, evidenced by the piracy of foreign games adapted and translated for a Brazilian audience. According to Renato Degiovani, a pioneer in game development in Brazil, there were two major electronics companies, Gradiente and Sharp, that manufactured computers in the MSX standard; they brought “suitcases of software” from overseas and distributed them to small Brazilian software companies.13 Then, these so-called softhouses, like Disprosoft, removed, or cracked, a game’s copy protection, often translating a game’s original content, altering title names, and replacing the original developer’s logo with their own.14 Large department and electronics stores, including Sears, then sold these products as if they were official.15 Magazines like Micro Sistemas, published during the 1980s, even featured ads from these softhouses promoting “their” games (fig. 11).

Figure 11

Disprosoft, one of the most prominent software houses in the Brazilian market during the 1980s, published advertisements for unlicensed video games, often cracked and translated into Portuguese. (Image courtesy of the author)

Some enthusiasts, however, took the risk of producing their own original games, giving rise to local development communities that were in turn supported by and flourished with the aid of enthusiast magazines, like Micro Sistemas. Yet these early works were text adventures set in local scenarios with local themes and without the appeal of provocative content so prevalent in mass media. It was as if they were seeking a unique identity in the new, unprecedented medium of computer games that differed from those already established in TV and cinema. Works like Amazônia from 1985, a text-based game in the style of the classic Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), were set against the backdrop of a labyrinthine Amazon rainforest inhabited by wild animals and Indigenous peoples. Games that followed in the wake of Amazônia were often inspired by famous places in Brazil. Examples include A Lenda da Gávea (1987), a text adventure exploring the urban legends surrounding the majestic Pedra da Gávea in Rio de Janeiro (fig. 12), and Av. Paulista (1986), a role-playing game set on São Paulo’s most famous avenue, considered one of the country’s major financial centers (fig. 13).This type of enthusiast, independent production began to lose traction in the second half of the 1980s when the country, transitioning to a democratic regime, inherited a challenging economic crisis from the dictatorship. In an attempt to tame the so-called inflation dragon—which caused prices to skyrocket overnight, eroded the value of fiat currency, and made uninvested money quickly lose its worth—Brazil embarked on a rollercoaster ride of economic plans and currency changes.16 This hindered the growth of the emerging game industry, affecting both smaller, enthusiast developers and large electronics manufacturers along with their affiliated game-cracking software houses.

Figure 12

A screenshot shows a scene from A Lenda da Gávea , a text adventure that explores local myths about a natural monument in Rio de Janeiro. ( A Lenda da Gávea [Renato Degiovani, Luiz F. Moraes, 1988]) (Screenshot courtesy of Generation MSX)

Figure 13

A screenshot of a menu featuring Portuguese-language options in the role-playing game Av. Paulista , set on Brazil’s most famous avenue, with references to real streets and venues ( Av. Paulista [Sysout, 1986]) (Screenshot courtesy of Bojogá)

At the same time, the National Informatics Policy, which had helped to cultivate a locally produced computer and electronics industry in the early 1980s, ceased to be a priority—especially after Apple and Microsoft pressured US president Ronald Reagan to threaten Brazil “in response to the maintenance ... of unfair trade practices in the area of computer products.”17 At that time, Apple was attempting to block the launch of a Brazilian Macintosh clone (the first to be announced worldwide) (fig. 14), while Microsoft was trying to block an operating system it claimed was a copy of MS-DOS.18

Figure 14

O Globo , one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers in the 1980s, reports on Apple’s accusation of illegal copying against the São Paulo–based company Unitron, which was manufacturing the first Macintosh clone. (Image courtesy of the author)

Brazilʼs first democratically elected president after the 1964 coup, Fernando Collor de Mello, would paradoxically only make matters worse for the local microcomputer industry in the early 1990s. On his first day in office, his administration confiscated the savings of all Brazilians in a radical attempt to control inflation by restricting the flow of money. Overnight, companies went bankrupt, and families lost their financial reserves, plunging the country into an atmosphere of insecurity and outrage.19 Furthermore, his economic agenda favored neoliberal policies, promoting an opening of the economy that benefited large foreign companies over national ones. This caused mass layoffs in Brazilian industries and ultimately buried the nascent Brazilian microcomputer industry, marking the end of the market reserve.

Thus, an emerging local gaming industry, which had been developing without the direct influence of Brazilian television, was thwarted by the numerous economic hardships Brazilians had to deal with in the second half of the 1980s and into the early 1990s. The cratering of the domestic microcomputer industry, and with it the local games of early developers, meant some companies’ early success never grew into more established businesses, and that these games’ various influences and tendrils never came to full fruition. Inevitably, games would return as the Brazilian economy evened out, but they would be accompanied by a new source of inspiration: television shows and celebrities.

Turning Toward Television

In 1994, a more consistent economic plan finally put the Brazilian economy back on track: the Real Plan, which stabilized the national currency and established the real as its official currency (still in use today). This moment coincides with the arrival of foreign home or personal computers in Brazilian stores, such as IBM, Compaq, Packard Bell, Acer, and other multinational brands. Just as Brazilians eagerly embraced freedom of expression with the end of the dictatorship, computer sales surged now that consumers were no longer restricted to national products and had the purchasing power to invest in a personal computer. At the same time, the mainstream media began portraying the PC as the “new member of the family” (fig.15), making it a central element even in a prime-time soap opera on Rede Globo.20

Figure 15

The July 1996 cover of IstoÉ , one of Brazil’s leading weekly magazines in the 1990s, claimed that computers were the “new member of the family.” (Photograph courtesy of Rosa Arrais)

Newly arrived computers became integrated in Brazilian homes as these devices shared space with the TV in living rooms. Incorporated by the middle class as a family item, the PC quickly became a highly desired consumer product, displayed prominently at the entrances of major supermarkets. With the market full of foreign software, including entertainment, there was a growing demand for games and programs in Brazilian Portuguese. “In the early 90s, it was important for you to have things in Portuguese,” noted prominent game developer and filmmaker Ale McHaddo decades later.21 She continued: “It was a way for you to stand out in relation to games and applications in general, especially for children who didn’t speak English.”

As local companies began to represent major international publishers in the Brazilian market, some of these international games were localized, as was the case with LucasArts’ point-and-click adventure game Full Throttle, released with Portuguese subtitles by Brasoft in 1995. “This was what started to make international games compete with national ones,” explained McHaddo, who believed that localization harmed the development of the national market. “I think it was for many reasons, but mainly due to the invasion of international products and dubbing. Localization itself began to make the differential [of the language] no longer exist.”

Due to their inability to compete directly with established international firms producing technologically superior game software, new local multimedia studios turned to mainstream Brazilian TV shows and celebrities, which were already established as a massive form of domestic popular entertainment. Lacking the technical expertise to create sophisticated engines, many studios made use of Macromedia Director, following a standard of the interactive multimedia CD-ROM containing simple collections of games and activities presented by characters or TV celebrities.

This era of production was characterized by the massive use of images, videos, and digitized voices of these popular figures, which distinguished national production from foreign games. For example, Gustavinho em o Enigma da Esfinge (Gustavinho and the Riddle of the Sphinx, 1996), featured the Brazilian actress Marisa Orth, notable for her role as the foolish and sexually insatiable female lead in the successful sitcom Sai de Baixo on Rede Globo (fig. 16). In the plot of the point-and-click adventure, the child protagonist insults an elderly man by calling him a mummy. As punishment, the boy is magically sent to Egypt (a “too Brazilian” script for the game to be released abroad, according to McHaddo).22 Orth’s casting as Cleopatra, the only life-like character, rendered as video in this otherwise cartoon-style illustrated children’s game, is an early example of televisual culture shaping the language of Brazilian video games during this period (fig. 17).

Figure 16

The front of the box for Gustavinho em O Enigma da Esfinge , one of the most successful Brazilian computer games of the 1990s, features Marisa Orth, a well-known TV actress. ( Gustavinho em O Enigma da Esfinge [44 Bico Largo, 1996]) (Image courtesy of Guilherme Chirinéa/Big Box PC Games Brasil)

Figure 17

Actress Marisa Orth plays Cleopatra, the only character depicted in live-action video in a game that otherwise has a cartoonish style ( Gustavinho em O Enigma da Esfinge [44 Bico Largo, 1996]) (Screenshot courtesy of the author)

Brazilian TV personalities also starred in their own CD-ROMs. Tiririca Interativo (1996) featured the comedian Tiririca, then famous on TV for his tacky songs, who narrated the userʼs actions in different activities and minigames. The CD-ROM also included video content of his humorous performances. Likewise, Angélica no Reino Animal (Angelica in the Animal Kingdom, 1997) similarly featured the childrenʼs TV host Angélica; it placed the player in both natural and surreal computer-generated environments, interspersed with minigames. In each activity, the host seemed to interact with the player, commenting on their actions and celebrating their victories.

This trend was strengthened in the late 1990s with the success of the computer-game series based on the Show do Milhão program, aired by SBT, the main competitor of Rede Globo (fig. 18). Replicating the format of the TV game show, which was inspired by Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, the game featured a quiz narrated by Silvio Santos, the host and owner of the network. Silvio Santos himself promoted the game during the highly popular show, and the product was also given as a bonus with the Computador do Milhão, a personal computer launched in a partnership between SBT and Microsoft, targeting lower and middle-income classes with an emphasis on digital inclusion.23

Figure 18

The box of the PC game Show do Milhão Volume 3 , based on the hit TV show. ( Show do Milhão Volume 3 [Abril Music, 2001]) (Image courtesy of cidraman/Internet Archive)

At the turn of the century, the Brazilian publisher Brasoft, which kickstarted the PC gaming market and became the largest software distributor in the country, saw its suppliers gradually become competitors; for example, Ubisoft and Electronic Arts established themselves in Brazil and managed their own local distribution. To survive, Brasoft was forced to belatedly invest in producing its own games.

Following the market logic of the time, it signed contracts with TV Globo and worked on adaptations of TV shows such as Big Brother Brasil (2002) and No Limite (2003), The Sims clones inspired by the broadcasterʼs reality shows. Targeting the youth audience, it commissioned the production of the 3D action game Vampiromania (2002), based on the soap opera O Beijo do Vampiro, and two games featuring the teen duo Sandy and Junior, who, besides being a musical phenomenon in Brazil, starred in a TV series and a sci-fi movie. These games, which attempted to emulate AAA adventure titles developed by experienced international studios, failed technically, artistically, and commercially, leading Brasoft to close its doors in 2004 after twenty years of operation.

Unsupervised Freedom

Although Brazilian television in the 1990s explored unprecedented freedom of expression, it was already a regulated medium, with content subject to age ratings established by the Ministry of Justice.24 Computer games, on the other hand, were part of a new, entirely unregulated environment, present in only a small fraction of households and, therefore, largely unsupervised. Indeed, although the media touted the computer as the “new member of the family” (see fig. 15), a survey published by Veja magazine showed that only 3.1 percent of Brazilian households owned computers as of mid-June 1995—approximately 1.24 million machines.25

Unlike other forms of entertainment, such as films and TV programs, computer games did not have mandatory age ratings until 2002, when the Ministry of Justice began imposing specific guidelines.26 This lack of regulation was evident in computer magazines accompanied by CD-ROMs, which, although they attracted a young audience with their games, often included content unsuitable for this demographic. Sold at affordable prices in newsstands scattered across the country—far more numerous than software stores—these magazines amplified the problem.27

In addition to the examples mentioned earlier, it was common to find advertisements for adult CD-ROMs or sexualized images in these magazines, some of which included partial nudity. Likewise, violent games appeared either as full versions or demos in each issue. This coexistence of such disparate content reflected an expanding market in which publishers prioritized sales volume over ensuring content was appropriate for their target audience. Alessandro Treguer, former editor of CD Expert, a major competitor to PC Multimídia and one of the most popular magazines in the segment at the time, confirmed that his readership was predominantly made up of children and teenagers, ranging from eight to seventeen years of age.28 Despite this, these publications often lacked warnings about inappropriate content for minors, implicitly relying on parents to filter the material.

In practice, however, the purchase and consumption of these materials were largely in the hands of young people. Treguer recounts that violent games like Blood—rated for ages seventeen and up in the United States and distributed in its full version by the magazine without an age classification—ended up in the hands of young readers.29 This paradox is evident in the illustrations sent by children to the magazine’s community section in the very issue featuring Blood (fig. 19).30

Figure 19

Drawings by readers published in CD Expert (no. 22, 1999) that included the game Blood , most of them made by children (Image courtesy of the author)

This scenario of unrestricted access explains how a game like Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal, filled with offensive humor, explicit sexuality, and problematic stereotypes, ended up in the hands of children across the country, unnoticed by the Ministry of Justice and overlooked by less attentive parents.

A Reflection of Its Time

Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal emerges as a product of this historical context. It brings together the provocative and sexually charged humor of TV, from which it originates, and indirectly evokes the sleazy style of pornochanchada at a moment of extreme freedom in a new medium, without the restrictions of age classification. In this unprecedented environment, the game did not have to follow quality standards and filters from Rede Globo. Thus, with its crude photographic montages, vulgar language, sexist humor, and high sexual content, the game heightened the political incorrectness of Casseta & Planeta, transgressing the limits already tempered by TV. Sold at newsstands as a mere gift of the then-popular magazines accompanied by CD-ROMs, Noite Animal easily ended up in the hands of children and adolescents.

Ironic as it may seem, even the most dedicated player would be unable to see all the raciest scenes or the most offensive jokes; reflecting an emerging industry with limited resources in the face of international competition, the game was so unstable that it crashed and flashed error messages at the slightest advancement by the player.

Analysis of Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal reveals more than just the limitations or excesses of a controversial game; it exposes a unique moment in the history of technology and mass culture in Brazil. In a post-dictatorship context marked by the return of freedom of expression and attempts to stabilize a devastated economy, the Brazilian computer-game industry found creative—and often chaotic—ways to exist. Without the technological advancements or resources available in countries of the Global North, Brazilian developers adapted tools and languages from their everyday reality to create products that directly resonated with their local audience. In this way, games like Noite Animal serve as testimonies to a singular domestic computing environment that, despite its flaws, deserves attention as part of a broader historical puzzle.

Footnotes

1. ^ Ministério do Planejamento e Orçamento, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE, Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios [National Household Sample Survey] 17, no. 1 (1995): 1–120, https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/59/pnad_1995_v17_n1_br.pdf.

2. ^ Although censorship as an institutional practice was extensively used by the military regime from 1964 onward, it was grounded in a decree established in the 1946 constitution, which created the Public Entertainment Censorship Service—known as the Public Entertainment Censorship Division during the dictatorship.

3. ^ Rede Globo supported the 1964 military coup, mainly due to the alignment of its founder, Roberto Marinho, with the regimeʼs ideals. Marinho feared the rise of a left-wing government and believed that the military coup would guarantee Brazilʼs political and economic stability. This support was strategic, as the network benefited from a close relationship with the government, which allowed for the modernization of its infrastructure and the acquisition of valuable concessions to expand its network of channels. In return, the regime benefited from the production of journalistic content favorable to the government, promoting a narrative of development and peace. The networkʼs growth and dominance in the Brazilian media, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, were largely a consequence of this alliance. In recognition of its mistake, Grupo Globo publicly apologized in 2013, admitting that its support for the dictatorship was a historical error.

4. ^ Eduardo Amando de Barros Filho, “O verde oliva na TV: O advento da televisão em cores pelo regime militar no Brasil,” Tempo & Argumento 13, no. 32 (January 2021), https://periodicos.udesc.br/index.php/tempo/article/view/2175180313322021e0204/12792.

5. ^ “O papel da TV Globo e o modelo Globo de televisão,” Cultura e Sociedade, Memórias da Ditadura, accessed March 27, 2025, https://memoriasdaditadura.org.br/cultura/o-papel-da-tv-globo-e-o-modelo-globo-de-televisao/#sobre.

6. ^ “Há 35 anos, Chacrinha investia em malícia e pisava no politicamente correto,” Notícias da TV, March 16, 2017, https://noticiasdatv.uol.com.br/noticia/televisao/ha-35-anos-chacrinha-investia-em-malicia-e-pisava-o-politicamente-correto-14447.

7. ^ Benjamin Cowan, Securing Sex: Morality and Repression in the Making of Cold War Brazil (University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 52.

8. ^ Tiago Dias, “Como a pornochanchada falou do Brasil sob ditadura militar entre cenas de sexo,” UOL Entretenimento, September 18, 2018, https://entretenimento.uol.com.br/noticias/redacao/2018/09/18/como-a-pornochanchada-falou-do-brasil-sob-ditadura-militar-entre-cenas-de-sexo.htm.

9. ^ This is not to say pornochanchada circulated uncensored. Films that strayed from the imposed content rules or openly expressed social critiques were mutilated and often ended up being shown in incomplete forms, becoming unintelligible.

10. ^ “Fantástico e a censura federal,” Memoria Globo, August 3, 2023, https://memoriaglobo.globo.com/jornalismo/jornalismo-e-telejornais/fantastico/noticia/fantastico-e-a-censura-federal.ghtml.

11. ^ This is especially true when evaluating film censorship across nations. Movies like Brokeback Mountain, Ted, and Fifty Shades of Grey have lower age ratings in Brazil compared to the United States, which is more restrictive regarding sexual content. On the other hand, Brazilian film ratings are stricter when it comes to films featuring gun violence, especially when compared to the US, where gun culture is deeply ingrained. This phenomenon stems from the influence of the dictatorship period on the formation of Brazilian mass culture.

12. ^ Reverse engineering is the process of disassembling and analyzing an existing product to understand how it works, replicate its functionality, or create something similar without direct access to the original plans or designs. It is widely used in technology to adapt or develop new products.

13. ^ Renato Degiovani, the creator of Amazonia, the first commercial computer game in Brazil, shares this and other details about the entertainment software market in Brazil in an interview for the author’s podcast Primeiro Contato. Henrique, Sampaio, host, Primeiro Contato, podcast, season 1, episode 1, “Computadores brasileiros,” July 19, 2021,13. ^ https://www.b9.com.br/shows/primeirocontato/primeiro-contato-1-computadores-brasileiros/

14. ^ During this period, software development companies, including video games, were referred to as “softhouses” in Brazil.

15. ^ The department store Sears had a Brazilian branch from 1949 to the start of the 1980s.

16. ^ “Plano cruzado, da euforia ao fiasco,” O Globo, July 28, 2013, https://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/fatos-historicos/plano-cruzado-da-euforia-ao-fiasco-9248088.

17. ^ Reagan, Ronald, “Statement on Trade Sanctions against Brazil,” November 13, 1987, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, Simi Valley, CA, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/statement-trade-sanctions-against-brazil.

18. ^ “Unitron Mac 512: A Contraband Mac 512K from Brazil,” Low End Mac, July 2, 2016, https://lowendmac.com/2016/unitron-mac-512-a-contraband-mac-512k-from-brazil.

19. ^ André Bernardo, “Entre infartos, falências e suicídios: OS 30 anos do confisco da poupança,” Universo Online, March 18, 2020, https://economia.uol.com.br/noticias/bbc/2020/03/17/entre-infartos-falencias-e-suicidios-os-30-anos-do-confisco-da-poupanca.htm.

20. ^ In Explode Coração, which aired in 1995, a woman from a Gypsy family becomes romantically involved with a businessman unfamiliar with her culture, whom she meets online. At that time, the internet was just beginning to operate in Brazil and was still a distant novelty for most Brazilian families.

21. ^ McHaddo was the creator of Gustavinho em o Enigma da Esfinge (1996), one of the most successful Brazilian computer games of the 1990s. She was interviewed for the author’s podcast. Henrique Sampaio, host, Primeiro Contato, podcast, season 1, episode 7, “Falado em Português,” September 13, 2021,21. ^ https://www.b9.com.br/shows/primeirocontato/primeiro-contato-7-falado-em-portugues.

22. ^ McHaddoʼs statement was also featured in Primeiro Contato, S1E7. In the context of Brazilian mass culture at the end of the twentieth century, even media products aimed at children often featured humor considered politically incorrect. A notable example is Turma da Mônica (Monica’s Gang), a famous and influential comic-book series created in 1970. The stories frequently revolved around the conflict between the characters Cebolinha and Cascão and the protagonist, Mônica. The two boys, who often called her “shorty,” “bucktooth,” and “chubby,” devised elaborate plans to steal her stuffed bunny, Sansão. However, their plans invariably failed, and the stories would end with Mônica retaliating and giving the boys a beating using Sansão himself.

23. ^ Márcio Padrão, “Como era o computador do milhão, iniciativa de Silvio Santos na tecnologia,” Universo Online, December 13, 2020, https://www.uol.com.br/tilt/noticias/redacao/2020/12/13/como-era-o-computador-do-milhao-iniciativa-de-silvio-santos-na-tecnologia.htm.

24. ^ “Classificação indicativa completa 30 anos,” Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública, October 28, 2020, https://www.gov.br/mj/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/classificacao-indicativa-completa-30-anos.

25. ^ “Survey,” Veja, June 21, 1995, 66.

26. ^ Guilherme Werneck, “Games terão classificação por faixa etária no Brasil,” Folha de S.Paulo, November 3, 2002, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/folha/informatica/ult124u9465.shtml.

27. ^ There were more than twenty-three thousand newsstands across the entire Brazilian territory in the year 2000, with the majority concentrated in the southeast region, especially in the state of São Paulo. According to a survey by Revista Banca Brasil, a publication from that time that specialized in the newsstand sector, in 2000, the state of São Paulo had 8,558 newsstands, more than the twenty-three states with fewer newsstands in the entire country. See Viktor Chagas, “Extra! Extra! Newsboys and Newsstands as Spaces of Dispute over the Control of Press Distribution and the Political Economy of the Media” (PhD diss., Fundação Getulio Vargas, 2013).

28. ^ Henrique Sampaio, host, Primeiro Contato, podcast, season 1, episode 10, “Pânico moral,” October 4, 2021,28. ^ https://www.b9.com.br/shows/primeirocontato/primeiro-contato-10-panico-moral/

29. ^ Henrique Sampaio, host, Primeiro Contato, podcast, season 1, episode 9, “Meninos radicais,” September 27, 2021, https://www.b9.com.br/shows/primeirocontato/primeiro-contato-9-meninos-radicais/

30. ^ Rodrigo Rudiguer, “Expert Artista,” CD Expert 3, no. 22 (1999): 9.

Jewel-case packaging of the CD-ROM Casseta & Planeta: Noite Animal (ATR Multimídia, 1995) (Courtesy of André Campos)