Abstract

Using a mixture of media archaeology and discourse analysis, I argue that the two most popular board games in ancient Greece, Five Lines (Pente Grammai) and City-State (Polis), had direct precursors in dynastic Egypt. I note that Plato's two speculative city-building dialogues—the Republic and the Laws—both engage in a "serious game" (in Plato's words) of imagining an ideal city, and each one mentions a different game as their referent (City-State is referenced in the Republic, and Pente Grammai is mentioned in the Laws). Through this comparison and references to other Greek literature modeled on games, I describe the central importance of games as models in early Greece. I argue that this understanding of games as models necessitates a reappraisal of game origins and patterns of transformation and that it reaffirms the necessity of game studies across disciplines.

Games are older than philosophy.1 When Socrates and Plato tried to imagine how a city-state should function, what justice means, how to cope with fate, or how to write laws, they were surrounded by examples of board games where players built competing city-states, argued about fairness, loaded their dice, and decided upon game rules. These gaming communities don’t make it into the acknowledgments of Plato’s Republic or his Laws, but that doesn’t make practices of gaming any less influential on Plato’s own city-building practices. In this article, I will be tracing the hidden history of philosophy by arguing that board and dice games originating in dynastic Egypt had a profound impact on both the content and the form of philosophical argumentation in the Platonic dialogues. To do so, I will examine the emergence of Greek games from out of the rich multicultural contact zone of the Mediterranean in the seventh century BCE. I suggest that the two most popular games during Plato’s time—City-State and Five Lines—were both influenced by prior Egyptian board games, and that Plato uses specific knowledge of these two games to model the narrative and central concepts of his Republic and Laws.2 The enormous impact these two texts have had on the past two millennia of social and political imaginaries makes the role of games in their production an urgent question in the present.

Greek Origins

To scholars in antiquity studying Greek culture, its cultural debt to dynastic Egypt was self-evident; as Greek historian Stanley M. Burstein has noted, references to Egyptian culture “occur in the works of almost every surviving classical author.”3 Similarly, archaeologist Richard Brown has cataloged over fifteen hundred Egyptian objects found in early Greek sites.4 Egyptian priestly wisdom was greatly prized by the Greek educated elite, and nearly every celebrated Greek thinker was said to have studied under the priests in Egypt (although at least some of these tales were fabricated).5 But in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, race science and nationalist ideology had conspired to choose Greece as a paradigmatic example of cultural autochthony.6 By the 1920s, classicist John Burnet was describing the emergence of Greek intellectual culture as a “Greek Miracle,” and Thomas L. Health similarly dubbed the Greeks as a “natural race of thinkers.”7 Thus, the attribution of origins—either to Greece or to foreign influence—has become highly politicized.8

In this article, I will be following a swath of excellent comparative work that has reversed this trend and resituated archaic and classical Greece as a multiethnic collision of cultures made possible by the traditions and trade routes across the ancient Mediterranean. At every turn, questions of what games are, what they do, and how they are developed have been central to these new histories of Greece. Classicist Emily Vermeule identified gaming burial objects and iconography in Greece likely originating in Egyptian mortuary practices and cosmologies, a connection further elaborated by Sarah P. Morris and John K. Papadopolous.9 The comparativist Martin Bernal suggested that these gaming objects provided evidence that the Greek concept of justice itself was influenced by earlier Egyptian gaming practices.10 Classics scholar Leslie Kurke links Greek games to competing models of political organization and the interpellation and reproduction of civic identity.11 Historian of mathematics Reviel Netz was instrumental in identifying a logical relationship between games and computational practices in early Greece.12 But a skeptical trend in the scholarship—most clearly represented by comparative archaeologist Walter Crist and Greek classicist Helène Whittaker—has suggested that games are the spontaneous outgrowth of any culture, and by implication, cannot be said to result from intercultural influences without explicit archaeological parallels.13

Game studies has much to offer this debate. Recent work on how we define games has brought into view the ideological stakes of such definitions.14 There is also a growing toolkit of concepts to aid historians of games in tracking the complex interplay of materiality and sociality at work among any community of gamers.15 I will be employing two concepts in particular in what follows: the “operational logics” of Noah Wardrip-Fruin in his description of the modeling capacity of games, and the concept of metagaming practices in the work of Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux. For Wardrip-Fruin, operational logics name the “foundational elements [of games] that do cultural work, that structure our understanding … in part through how they function computationally.”16 This is to say, the procedural operations one follows when playing out game rules—and the resulting cultural logics these operations produce—are a way of describing the basic elements of games as modeling instruments. I find this insistence on the cultural context of gaming practices is complemented by Boluk and LeMieux’s sharpening of the term metagame to encompass “the contextual, site-specific, and historical attributes of human (and nonhuman) play.”17 Metagaming as an historical method rejects “the authority of [games] as authored objects,” affirming instead the constant experimentation, rearticulation, borrowing, and repurposing of gaming technologies in service of play.18

My history of Greek games will accordingly refuse a single-minded preoccupation with material objects to focus instead on the broader contexts of play that helped to prompt various innovations and alterations in gaming technologies from dynastic Egypt to archaic Greece, and on the conceptual outcomes of operational logics as they propagated through cultures as playable models. Through a comparison of metagaming practices and operational logics in the two most popular Greek board games—City-State and Five Lines—and a number of Egyptian board games—especially Passing, Endurance, and an unnamed game of thirty-three squares—I hope to demonstrate a highly plausible relationship between the games of these two regions.

Greek Board Games: City-State and Five Lines

Only two board games in ancient Greece are widely attested by some combination of archaeological and textual evidence. The first—called Cross-Lines (Diagrammiomos) more generally, or City-State (Polis) more specifically—was a two-player strategy game played upon a rectangular grid of a variable number of squares with up to thirty game pieces (called “dogs”) for each player (see fig. 1). In addition to the rectangular grid, another element of the game is the core operational logic of capture, which was accomplished by surrounding an opponent’s isolated dog with two of one’s own. Game historians generally agree that the primary objective of the game is connecting one’s dogs by moving them to adjacent squares while preventing one’s opponent from doing the same by capturing their isolated pieces and perhaps by corralling them to the corners of the board. The board itself might have been referred to as a City-State (Polis), but it is also likely that the connected groups of dogs for each player were referred to as city-states (poleis). While historians at the turn of the twentieth century followed R. G. Austin’s a priori assumption that this strategy game involved no element of chance, current scholars have increasingly recognized that randomization instruments were used—either dice or astragaloi (animal anklebones)—although the function they served is a matter of speculation.19

Figure 1

City-State developed no later than the fifth century BCE, within a century of the establishment of democracy in Athens. Greek classicist Max Nelson links the two, noting that early references to the game in dramas by Cratinus and Euripides associate the game with the acts of King Theseus, who was known for uniting the numerous communities (poleis) into a single Athenian city-state (polis).20 Kurke strikes a symbolic comparison between City-State and Five Lines, arguing that City-State—with its undifferentiated game pieces and central objective of factional unification—was considered by Greek writers to be a model for democracy itself, and they often contrasted it with Five Lines, which bore aristocratic and cosmologically oriented overtones.21 The descriptive challenge for game historians has been twofold: first, a dearth of examples of gridded game boards in classical Greece—only three tentatively connected to the game, none of which are confirmed through accompanying description—and second, the close resemblance between City-State and the Roman Game of Brigands (ludus latrunculorum), the latter of which is likely to have been based on the former.22 Thus, gridded boards before the second century BCE can only be assumed to be examples of City-State, and gridded boards from the second century on might be examples of either game.

With Five Lines (fig. 2), the situation is much clearer, thanks largely to its popularity as a funerary votive offering in the seventh through fifth centuries BCE, and the exhaustive cataloguing of Ulrich Schädler and collaborators.23 The game, also involving two players, was one of mixed strategy and chance akin to backgammon (to which it is arguably a direct predecessor). The name Five Lines is misleading, however, because archaeological finds of matching game boards often depict seven, nine, or eleven lines. Each player, using five pieces, would attempt to move each of their pieces around the board according to the roll of one to three dice, likely in a counterclockwise rotation down one side of lines and up the other, ending by landing on the middle line (the so-called holy line). In plausible reconstructions of the rules by Schädler, Stephen Kidd, and Max Nelson, among others, textual references to the game seem to indicate that players won when all five of their pieces landed on the holy line.24 However, a risky strategy was occasionally practiced where a piece could be moved away from the holy line in order to battle an opponent’s piece (which was either rendered immobile or perhaps knocked off the board).

Figure 2

Example of terracotta Five Lines game from the Archaic period (ca. early 6th century BCE) (Courtesy of the National Museum of Denmark)

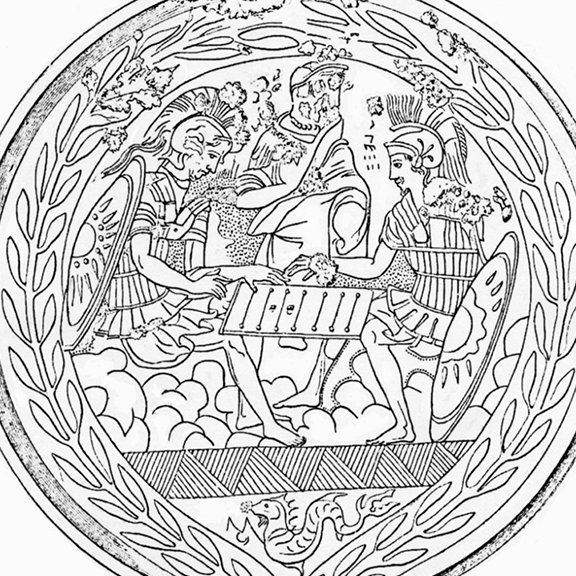

Through a careful examination of textual evidence, Max Nelson has recently claimed that Five Lines was also called Ship-Battle (Naumachia) at least as early as the second century BCE.25 By Nelson’s reckoning, the game depicted a naval battle either through a series of lines or two divisions of round indentations that formed a circle.26 In addition to this probable nautical association, the game was also strongly associated with Greek cosmologies. Beyond the semifrequent offering of terracotta votive game boards at archaic gravesites and the aristocratic symbolism of the game, researchers have found the game depicted in the immensely popular gaming scene between Achilles and Ajax, of which there are at least 168 examples (see fig. 3).27 Thus, the game bore strong symbolic associations with the afterlife and one’s fate.

Figure 3

Two warriors (likely Ajax and Achilles) playing Five Lines on a bronze Etruscsan mirror (Gustav Körte, Etruskische Spiegel , vol. 5 [Berlin, 1897], pl. 109)

Egyptian Board Games: Passing and Endurance

The Egyptian game of Passing (sn.t in demotic Egyptian, generally called Senet) is perhaps the most commonly known of the games I will discuss. The earliest verified depictions of the game date to the Third Dynasty (ca. 2686 BCE), and the latest to the fourth century BCE, making it the longest continuously played game in Egyptian history.28 The board was characteristically a three-by-ten rectangular grid of squares, and each player attempted to navigate between five and seven game pieces (originally called “dancers,” but by the middle of the second millennium primarily called “jackals” or “hounds”). The pieces moved in a boustrophedon (there-and-back) way from the beginning of the board to its end based first on the casting of four sticks, then later the casting of teetotums and knucklebones. The goal of the game was for all of one’s jackals/hounds to exit the board at the last of the thirty squares. Various perils were marked by hieroglyphs on the board and could cause the game piece to be frozen in place, sent back a number of squares, or even removed from the board. Additionally, one’s opponent could immobilize one’s pieces by surrounding them, displace them backward by landing on their square, and perhaps even knock them off the board through these means.29

The cosmological significance of Passing is widely acknowledged. While the game had an enduring association with offering rituals linked to the goddess Hathor that were intended as provisions for the deceased on their journey through the netherworld, it seems to have only gained a symbolic association with passage through the netherworld itself by assimilating these features from the game of the snake-god, Mehen, at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.30 The game reached its symbolic apex during the New Kingdom, where it was featured in a spell from the Coffin Texts that allowed one to play against one’s deceased relative; it was also depicted in a vignette from the Book of Going Forth by Day (a.k.a. the Book of the Dead); and it was the subject of a fairly extensive priestly ritual called by historians the “Great Game Text.”31 By the beginning of the first millennium, Passing was played by people of every social stratum—from the ornate game box of King Tutankhamun to graffito boards etched onto walls and city streets. The thirty squares on the board mirrored both the classical divisions of the kingdom into thirty districts (or nomes) as well as the division of the netherworld into thirty houses, each inhabited by a different god whose favor was necessary for players to be declared “justified” and complete their nether journey.32 At the height of its popularity, royals and high officials were commonly depicted on tombs playing Passing alone or against their own bꜣ (spiritual life force), as a way of training for their journey through the netherworld.

Compared to the extensive archaeological, pictorial, and textual evidence of Passing, the game of Endurance is practically unknown.33 The first mention of Endurance appears in a list of offerings at the tomb of the Fourth Dynasty prince Rahotep (ca. twenty-seventh through twenty-sixth centuries BCE) along with the games of Passing and Mehen. Egyptologists have connected this information with a painting of gaming equipment in the Third Dynasty tomb of the high official Hesy-Re (ca. twenty-seventh century BCE). This painting (fig. 4) depicts a Passing board with two sets of seven dancers and four casting sticks; a Mehen board with two sets of eighteen marbles and six couchant lions; and a rectangular board with sixteen transverse lines with two sets of five accompanying gaming tokens that can be identified as Endurance. The number of lines on examples of Endurance boards also varied. While two early instances of the board feature an even number of lines (the sixteen-line board mentioned above, as well as a board of ten lines dating to First Dynasty, ca. 3000 BCE), the intact board found in the Royal Cemetery in Nubia bears fifteen transverse indentations.

Figure 4

Drawing of a painting from the tomb of Hesy-Re (27th century BCE) depicting the games of Passing (left), Mehen (bottom), and Endurance (top right) (J. E. Quibell, Excavations at Saqqara [1911–1912]: The Tomb of Hesy [Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1913], pl. 9)

The context of both early finds alongside two other games associated with the afterlife has led several Egyptologists to infer that the game of Endurance bore a related symbolic importance. This association is reinforced by the analysis of gaming pieces also named endurance (mn in demotic) conspicuously displayed along the doorways of inner burial chambers. Peter Piccione argues that these gaming pieces symbolized the endurance of the bꜣ (spiritual life force) after death.34 The significance of Endurance was further elaborated by the tentative identification of an Endurance game being played on a model warship from a First Intermediate Period burial (twenty-second through twenty-first centuries BCE (fig. 5).35 This is the latest example of an Endurance board before the game apparently faded from popularity in Egypt. Notably, the board is painted with nine transverse lines—a second example of a rectangular board with an odd number of lines. The presence of an Endurance board on a warship suggests an additional martial association that neither Passing nor Mehen seemed to have at the time.

Figure 5

Model of military transport ship likely depicting an ongoing game of Endurance, First Intermediate Period (ca. 22nd–21st centuries BCE), Ashmolean Museum (Photos courtesy of author)

Metagaming in Egypt

While the continual entanglement of Passing with other games and practices is a central feature of its millennia-long history, both Egyptologists and Greek classicists have resisted seeking routes of intercultural influence. I will thus begin my case for the relationship between Egyptian and Greek games by describing Passing within its network of associations—not as a modern game with fixed rules and boundaries, but rather as a tool for creating metagames and other practices. This new perspective will help us appreciate the extent to which game forms, logics, and imaginaries travel, and to what models and concepts they give rise.

Of the three games noted in the Old Kingdom offering inventories mentioned above, only examples of Mehen survive from the Predynastic Period (before 3100 BCE). However, several fragmentary boards resembling Passing have been found in First and Second Dynasty tombs, suggesting a similarly ancient provenance for the game.36 Additionally, a three-by-six clay board and twelve conical pieces bearing a strong resemblance to Passing, excavated from a predynastic grave at el-Mahasna, have been connected to Passing by a number of Egyptologists, both for their formal elements and their strong resemblance to other ritual objects used in offering rituals.37 The change in form to a three-by-ten game board in the first dynasties was arguably an intentional project to alter the form of a preexisting game to conform to a symbol of central dynastic importance: the number thirty. Early in the dynastic period, Egypt adopted a twelve-month and thirty-day calendar and appointed a so-called Council of Thirty to preside over the administrative districts. The netherworld was analogously described as a site of thirty rooms ruled over by thirty gods.38 Thus, the thirty squares of the Passing board could function as a tool for calendrical reckoning or as a model of the correspondence between civic geographies and sovereignty in this world and the one beyond. In addition to its enduring relation to the offering ritual, the game of Passing also adopted these calendrical, geometrical, and spiritual associations through its numerological significance.

The flexible usage of the thirty-square Passing board can also help to explain why it became the site of a variety of metagaming practices. By the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (twenty-first century BCE), the games of Mehen and Endurance had disappeared, but key features of their symbolism and gameplay were incorporated into Passing. While Mehen in the Old Kingdom was the game that high officials and royals played to prepare for the netherworld journey, Passing had usurped this role in the Middle Kingdom, as changes in belief gave a wider circle of society a role in the afterlife. Mehen remained the god of netherworld protection even after his eponymous game fell into disuse, and after that he became the Egyptian god of games in general—and one’s sparring partner during ritual play of Passing who would grant winners protection in the netherworld and declare them justified (ma’a cherou).39 The transmission of esoteric knowledge of the netherworld through the game of Mehen was also emulated by Passing in the Middle Kingdom.40 This persistence of Mehen as the god of games across game platforms helps to reinforce my emphasis on broader metagaming practices rather than a narrow view of comparable archaeological materials.

Changes to Passing during the Middle Kingdom also provide evidence that it had absorbed some of the functions and symbolism of Endurance. While Passing in the Old Kingdom was a game played with seven dancer game pieces per side, by the Middle Kingdom it was almost exclusively played with five pieces per side, which were now commonly described with the hieroglyph for endurance and likened to an undying soul. Both of these changes support the idea that Passing became a platform upon which the logics of both Mehen and Endurance could be expressed. The nine-line configuration of the Endurance board on the model warship discussed above could indicate that later instances of the game were abbreviated to correspond to the nine divisions between the ten rows of squares on a Passing board.

Between the end of the Middle Kingdom (eighteenth century BCE) and the end of the Late Period (fourth century BCE), Egypt witnessed an explosion of gaming practices, variants, and experimental shifts in game design. But Passing retained its role as the locus of these transformations. Beginning in the Second Intermediate Period (sixteenth century BCE), the foreign twenty-square game Four Rooms began to appear opposite Passing on the newly designed gaming boxes.41 This game gave rise to two others as it faded from view in the twelfth century BCE: a game of thirty-one squares and a game on a three-by-eleven grid, both of which were nearly always found opposite Passing on gaming slabs.42 The Great Game Text that detailed a ritual involving the game of Passing also included depictions of the game that historians have referred to as “Hounds and Jackals” and this thirty-one square game board.43 In the Late Period, a new board of three-by-twelve squares began to appear that allowed gamers to play Four Rooms or Passing interchangeably, depending on which squares were considered active.44 Thus, the history of gaming in Egypt is a history of three millennia of metagaming practices. The Egyptian contribution to the history of games is not merely in the material artifacts of its games but in the imaginative production and reappropriation of gaming technologies to serve different ends in different moments. The versatility of Passing as a modeling technology made it the earliest recorded gaming console in human history.

The Case for Egyptian Influences on Greek Games

In this section, I will make the case that Egyptian (and Southwest Asian) gaming traditions did indeed influence the development of Greek games. While the archaeological and textual evidence I introduce below has been sporadically discussed by other historians of games, I will combine an appreciation for metagaming practices with an analysis of specific operational logics to make the novel argument that the functions, symbolism, and affordances of Passing and the unnamed three-by-eleven game were employed in the development of City-State and Five Lines, respectively. In the final section, I will investigate specific operational logics shared between games through a reading of Plato’s Republic and Laws, thus supporting the claim that early Greek philosophy drew upon models and logics developed by Egyptian gamers.

Attributions by Contemporaneous Sources

At the beginning of Socrates’s Egyptian myth in Plato’s Phaedrus, he tells of the god Thoth, who “invented numbers and arithmetic and geometry and astronomy, also draughts [pessoi] and dice [kuboi], and, most important of all, letters.”45 This oft-referenced attribution of Egyptian origins to Greek games is central to our search for influences, so it deserves further consideration. First, it is important to note Plato’s extensive familiarity and engagement with Egyptian wisdom, as evidenced by the Phaedrus in particular and throughout his dialogues. As noted above, the high reputation of Egyptian knowledge in classical Greece gave rise to wide reportage of travels to Egypt for the purpose of training under the priestly literati. While scholars disagree about whether Plato himself studied under the priests of Egypt—as many sources in antiquity state—it is widely recognized that his student and longtime interlocutor, the geometer Eudoxus, received extensive education in Egypt.46 This relationship also helps to contextualize the central role of geometry in Platonic cosmology in the later dialogues—a connection to which we will return.

Second, this is not a solitary attribution by Plato, but it corresponds to numerous other descriptions of Egyptian games in his writings. There are two extensive discussions in the Republic and the Laws on the use of play in Egyptian pedagogy—specifically, the teaching of arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy—which Plato associates with Greek board games. In addition, the Byzantine theologian Eustathius of Thessalonica, responsible for much of our surviving knowledge of Plato’s works, quotes a description by Plato of a board “marked as though it were a game of draughts … by means of which the Egyptians treat the movements of the sun, and of the moon and the eclipses.”47 Piccione has identified the game board Plato describes here as a Passing board based on its similarity to a board mentioned in the Ptolemaic Oxyrhynchus fragments. The latter fragmentary papyrus depicts a board comprised of thirty squares used in ancient Egypt for calculations related to the synodical (thirty-day) month, which had counters of opposing colors called “dogs.” The final square of the board was called the “house of Horus,” which exactly matches the name of the square in Passing. Bernard Grenfell notes in his edition that this fragment was likely translated from the Books of Thoth, a series of esoteric texts that formed the basis for Hermeticism.48

Third, Thoth’s list of inventions corresponds to a series of earlier descriptions of Greek inventions attributed to the cultural hero Palamedes beginning with Sophocles, most of which included games with stones (pessoi) and dice (kuboi). The famed orator Gorgias wrote a playful legal defense in the voice of Palamedes, describing himself as “[a] benefactor of Greece, present and future, by reason of my inventions, in tactics, law, letters (the tool of memory), measures (arbiters of business dealings), number (the guardian of property), beacon-fires (the best and swiftest messengers), and the game of draughts as a pastime.”49 Plato indicates knowledge of this tradition when he repeats this list in his eponymous dialogue Gorgias. Thus, Plato’s contemporaries would have read the attribution of these inventions to the Egyptian god Thoth as an outright rejection of local invention myths.

Despite the common assumption that these stories about Palamedes support the case for a Greek invention of games, I am suggesting they help unravel the opposition between foreign import and local invention that is characteristic of reductive understandings of games as stable objects. The presence of writing and mathematics on these lists helps to reinforce this point: both the Greek alphabet and the techne of arithmetic and geometry were understood by contemporary sources as deriving from northwest Semitic and Egyptian sources.50 Even stories of Palamedes’s invention of board games describe this event as happening during the Trojan war as a method of keeping the soldiers entertained.51 This context can help us understand what the invention of games might have indicated for Greek contemporaries, who no doubt heard tales from travelers to Egypt who had seen truly ancient scenes of royals and high officials playing the game of Passing painted on temple walls. Plato’s extensive knowledge of Egypt positioned him to set the record straight concerning the origins of Greek games.

There is another textual source that can help us to connect Greek and Egyptian games and that also provides an example of the shared symbolism and operational logics present in the games. The fifth-century BCE play by Aeschylus, The Suppliant Women, begins by describing a Egyptian man of Greek ancestry who flees Egypt with his daughters to avoid their marriage to their cousins, sons of his brother Aegyptus. From the first lines of Aeschylus’s Supplices, we are told that the protagonist, the Egyptian Danaus, arranges for his daughters’ passage by ship to Greece as though they were game pieces.52 Geoffrey Bakewell has recently argued that this trope of Danaus directing his daughters’ actions as though he were playing a board game develops into a central motif throughout the play.53 The dramatic action of the group moving toward the altars at the center of the city mimics for Bakewell the goal of Five Lines—to find sanctuary upon the holy line. From the repeated invocation of the importance of good fortune on the outcome to a xenophobic contrast drawn between the rapacious “dogs” of Egypt and the “wolves” of Argos, the play continually employs the operational logics of board games into the plot movements of Egyptian refugees.54 This formula would prove highly influential for the next generation of dramatists; we see the trope connecting foreign suppliants with board games recur in Euripides’s Suppliants and playfully subverted in Cratinus’s Run-Aways.55 When paired with the foreign attribution of board games by Herodotus in his Histories, this tradition indicates that by the time Plato was writing his Phaedrus, his readers would already have a web of associations linking games to foreign notions of cosmic and political order.56

Formal Resemblances

That both the City-State and Five Lines game boards displayed such a great amount of formal variance in itself suggests the possibility that the games were developed from earlier models in other locales. Likely examples of City-State boards (or its close relative, the Roman Game of Brigands) are grids of three by five, six by eight, eight by eight, eleven by eleven, eleven by twelve, and other variations.57 Similarly, Five Lines, despite its name, was played on boards of eleven, nine, seven, or five lines, and perhaps even on a circular pattern of ten cups.58 By contrast, de Voogt and colleagues have noted the high degree of regularity in board-game artifacts that have been found across the Mediterranean.59 Other popular games like Passing, Four Rooms, and “Hounds and Jackals” tended to retain spatial relationships between the number and configuration of cells because they held numerological associations to calendrical, astrological, and political formations. The absence of these restrictions in Greek games reinforces the importance of the operational logics of the games themselves. Moreover, it suggests that the numerology of the boards was subordinated to the underlying spatial logics themselves—those of grids and lines.

A rare exception to this general rule will prove central to finding commonalities across game cultures: a marble slab from Greek Thrace with two games etched onto it, identified as Five Lines and City-State (fig. 6). The Five Lines board has eleven lines, with an X in the middle of the third, sixth, and ninth lines—a pattern also present in two examples from Cyprus.60 The City-State board next to it is a roughly incised three-by-five grid of squares. By recalling the possibility raised by the game of Endurance—that a game of lines could be represented on other game boards, or even serve as an abbreviated form of those games—we can compare this distinctive pattern of lines and X’s with a three-by-eleven game board from Egypt dated between the twelfth to eleventh centuries BCE (fig. 6). We observe that the rosettes on the Egyptian board are at the precise locations of the later example from Thrace—the third, sixth, and ninth rows.61 Historians of mathematics have interpreted this pattern of rows and X’s as a method of arithmetical calculation akin to an abacus. The mark on the center row of the three-by-eleven board—found even on examples without all three marks—suggests that the board configuration of eleven-row Five Lines proposed in reconstructions, where each player would use five rows and meet on the so-called sacred line at the center, was also accommodated by the Egyptian three-by-eleven board in the centuries prior.62

Figure 6

Left: Marble gaming table depicting Five Lines and City-State from Thrace, Abdera Museum. (Image copyright Greek Ministry of Culture; monument under authority of Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports/Ephorate of Antiquities of Xanthi [MA 3498]. Used by permission); right: Egyptian game board of thirty-three cells (ca. 12th–11th centuries BCE) (Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

In addition to these operational parallels, both examples are juxtaposed with grid-based games: the three-by-eleven board is etched onto a slab with three-by-ten Passing on the reverse side, and the Five Lines slab is adjacent to a three-by-five City-State game—exactly half the length of a Passing board.63 While we have no direct evidence of a revival of Endurance during this period of Egypt, it is significant that the two later examples of the game also depicted an odd number of lines, and that the nine-line configuration of the model warship game is also shared by an early terracotta Five Lines board (fig. 2). Furthermore, no other examples have emerged of rectangular grid-based games or rectangular line games in the Mediterranean other than Passing and Endurance, two games originating in Egypt.

Routes of Transmission and Cultural Interactions

Due to the regional dominance of Egypt for several extended periods of its three-millennia-long dynastic period, examples of Egyptian games—including Passing, Mehen, and another game referred to as “Hounds and Jackals”—have been identified throughout the Mediterranean and West Asia, dating from the early third millennium BCE to the beginning of the first millennium BCE.64 As such, the latent possibility of encountering and adopting Egyptian gaming practices was present throughout the history of Greece. The earliest archaeological evidence we have for Passing outside of Egypt is in the Levant, dated to the beginning of the third millennium BCE, and further examples of the game have been found throughout Southwest Asia in the following two millennia.65 Bronze Age Cypriots in particular appear to have appropriated Passing and Mehen into their own cultural practices.66 Niklas Hillbom concludes his definitive study of games from Minoan Crete by arguing that a direct line from Egyptian games is highly likely, considering the typological resemblances between Minoan game samples—some as late as the fifteenth to twelfth centuries BCE—and the games of Passing and Mehen.67 It seems unlikely that Greece would be the only region completely unaware of Egyptian gaming practices while developing its own.

Instead, it is much more plausible that Hellenes had several phases of interactions with Egypt, each with their own influences. This much seems likely based on the work of Sarah P. Morris and John K. Papadopolous on the one hand and Emily Vermeule on the other. Morris and Papadopolous trace a gradual appropriation of Egyptian gaming scenes and instruments along trade routes at the beginning of the Geometric Period (ninth century BCE), noting Egyptian objects were seen as status symbols among the Panhellenic elite in the Aegean during this period (and long after).68 Indeed, the state of Ionia in Greece was the primary trading partner of Egypt during the seventh century, and this trade happened both directly through the Egyptian trade city Naukratis and indirectly through the Phoenician merchants of the Levant.69 Vermeule likewise examines several examples of seventh to sixth century BCE votive game boards and images of gaming that exhibit allusions to the afterlife, a metaphorical complex she links to Egypt.70 This observation agrees with the broader appreciation of Egypt among Greek elites, which has influenced Greek science, technology, poetry, art, religion, legal thought, and more.71

To this constellation of intercultural interactions, I would add what I believe to be a direct link to Egyptian games that aligns with the emergence of Five Lines and City-State and also comports with their origin stories: the return of Greek mercenaries who famously assisted the Late Period king Psamtik I in expelling Assyrian invaders and restoring Egypt to indigenous rule in 664 BCE. The early seventh century corresponds both to the last examples of Passing and accompanying three-by-eleven boards in Egypt and also the earliest mentions of Five Lines in Greece.72 Moreover, two wooden plates with Passing boards incised into them have been recovered from a dig at the fortress at Tell Defenneh, which housed Greek mercenaries during this same military operation.73 Whether soldiers brought examples of the game home with them is impossible to say at present, but they unquestionably came across Passing and likely had a similar encounter with a three-by-eleven board due to its popularity and common association with Passing at the time. This link between Egyptian and Greek games during wartime also helps to explain both the attribution of the invention of games to Palamedes while he was away at the Trojan War and the pervasive martial symbolism and mechanics present in both games. In an ancient example of intercultural metagaming, garrisons of Egyptian and Greek soldiers could have collaboratively repurposed the gridded space of Passing and its operational logics of surrounding to model a new situation: a land war of fragmentation and unification.

Shared Symbolism and Uses

Greek classicists generally agree about the close symbolic parallels between Greek games found in burials and earlier Egyptian examples. The Five Lines gaming scene between Achilles and Ajax in particular (fig. 2) was among the most popular depictions on black-figure vase offerings in the classical period, and they carried strong associations with themes of fate, justice, and the afterlife. These themes are further reinforced in other variations of this scene, where two warriors in similar poses are undertaking divination about the upcoming battle or casting votes, represented by stones, in the trial of Achilles.74 The common thread of these depictions is the pessoi gaming pieces, which were also used for counting and tallying of all kinds—from mathematics to divination and voting.75

As evinced by Plato’s many references to board games during discussions of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and justice, Greek games bore a strong symbolic and practical association with these other arts. Further evidence from other Greek sources reinforces this connection. Timaios’s Lexicon of Platonic Words, written in the first centuries CE, mentions that a Greek board game (likely City-State) was also referred to as “geometry.”76 This connection should not be surprising, considering the recent find of a marble engraving of a geometry lesson featuring a teacher pointing at a ten-by-ten grid inscribed with numbers, in addition to a gridded board with engraved numbers that was identified as City-State.77 Diorodus Cronus, a philosopher of the Megarian school and a disciple of Aristotle, likened the movements of counters to the movements of the stars.78 Jean Taillardat notes that Diodorus Cronus participated in fourth-century philosophical debates on the possibility of movement, suggesting Five Lines was used as an illustration of cosmic principles in these debates. Clearchus of Soloi, a fifth to fourth century BCE general, similarly declared that the five counters were analogous to the five planets.79 Five Lines boards have also been the subject of extensive reconstructions by historians of mathematics, who note their use as computational instruments. Véronique Dasen and Jérôme Gavin describe the resonances of civic and cosmic order shared between abaci and games.80

The evocation of competing models of civic order became a central theme in classical references to City-State and Five Lines. Kurke observes the common use of City-State as a metaphor for democracy and the contrasting tendency to reference Five Lines as a metaphor of aristocratic hierarchies. City-State in its gridded regularity and logic of consolidation, and Five Lines with the movement toward its central holy line, both modeled competing civic geographies and concepts of justice—a central theme in Plato’s Republic and Laws.81

The exigencies of preservation have resulted in a wealth of information about Egyptian mortuary culture—preserved in stone tombs—and a relative dearth of information about other aspects of everyday life and intellectual culture, such as calculation and administrative practices; nonetheless, the connection to Egypt remains evident in all of the above. The use of Passing boards to represent the thirty-day calendar (and also eventually the yearly calendar), the Council of Thirty of administrative Egypt, and the thirty houses of gods in the netherworld are all established. It would be a small leap to see in this gridded abstraction of the state a tool for calculating volumes and angular geometries. Finally, translations of the Great Game Text have revealed details of a New Kingdom ritual involving the game of Passing, where after completion of the game, the god Mehen declares the player ma’a cherou (mꜣꜥ ḫrw in demotic, “to be justified, vindicated, triumphant”). This phrase matches the proclamation of the god Anubis after the completion of one’s trial in the netherworld. But more importantly, it has also been identified as the etymological origin of the Greek appellation “blessed” (makarios), which bore a similar significance in Greek cosmologies.82 Thus, geometry, astronomy, and justice are all closely associated with the symbolism and use of Passing.

Little is known about either the ancient game of Endurance or the Late Period game of three-by-eleven, but we can say, first, that Endurance is the only clear Mediterranean example of a game associated with naval warfare prior to Five Lines and that Aeschylus’s Suppliant Women uses the verb for “moving game pieces” in a reference to sea travel from Egypt. Second, Egyptian and Greek calculating practices were quite comparable, as indicated by the historian Herodotus after his journey to Egypt (ca. 425 BCE), who noted that “in writing and in reckoning with pebbles, the Hellenes move[d] the hand from left to right, but the Egyptians from right to left.”83 Consequently, the patient reconstruction of Greek computational practices by historians of mathematics might also help to illuminate Egyptian computation on three-by-eleven boards in the Late Period. Further, both Greece and Egypt were likely influenced by the highly advanced Babylonian algorithmic methods, and the ludic abacus of eleven rows shared between Five Lines and the Egyptian three-by-eleven board probably originated in earlier numerical sequences inherited from the Southwest Asian game of Four Rooms.84 Similarly, the invention of cubic dice, which were a central feature in Five Lines and perhaps also in City-State, was almost certainly another product of Southwest Asia. Thus, while the transmission of Egyptian gaming practices before, during, and after the seventh-century campaign of King Psamtik I is highly likely, we must “think more ‘triangularly’” about the rich intercultural environment of the Mediterranean in the final tally.85

Games as Models for Philosophy: Plato’s Republic and Laws

“[T]he first of Plato’s interpreters, Crantor[,] says that [Plato] was actually mocked by his contemporaries for not having discovered his constitution himself, but having translated the [ideas] of the Egyptians.” —Proclus, fifth century CE86

This final section will propose that an investigation into the game imaginaries that Plato employs in his modeling of the ideal state can contribute to the growing recognition of Egyptian influences upon Greek philosophy. I will suggest that the central motif in both the Republic and the Laws is that philosophers play a verbal game in the construction of the ideal state, but more specifically, that the Republic takes as its model the game of City-State, and the Laws is similarly modeled on the game of Five Lines. Rather than deploying an idle metaphor, I argue that Plato models conceptual, practical, and rhetorical aspects of the two dialogues on specific operational logics of the two games. While the previous section determined the high likelihood of an Egyptian influence upon Greek game cultures, this section will emphasize the broader game imaginaries that Plato evokes, which by his own accounting are undeniably Egyptian.87 Through an investigation of the influence of game models upon the origins of Greek philosophy, I hope to illustrate the profound influence of games on the knowledges and institutions of the present.

Justice as an Operational Logic in Plato’s Republic

Like the marble tablet inscribed with a three-by-five City-State board and an eleven-line Five Lines board mentioned above, Plato’s Republic also takes place in the region of Thrace—at the commercial district trafficking in foreign goods. This border location helps to reinforce the growing recognition by comparativists that this text looks outside of Greece for a new conception of justice. The Latin title, Republica, obscures an important connection conveyed by the Greek Poleteia, which is that the entire dialogue focuses on the role of justice as a relationship between the various citizens of the polis (city-state). To define justice, Socrates proposes that he and his interlocutors should “make a city in speech (logos) from the beginning,” and thereby identify the moment justice comes into being.88 Crucially, this model city is also necessary for the education of the city’s children, who bear the stamp of whichever model they are given.89 Thus, the production of justice in their model city also continually discusses the reproduction of justice through the application of models. Socrates outlaws certain kinds of music to ensure the children engage in “more lawful play”; insists upon making children “spectators of war” to prepare them; and proposes using play, rather than force, as a tool for instruction.90 This connection between justice and play becomes a central theme for the remainder of the text.

The dialogue oscillates between the content of discussion and its form—a playful mock trial of Socrates—through continual punning wordplay and examples. Already in book 1, Socrates asks, “Is the just man a good and useful partner in setting down draughts, or is it the skilled player of draughts?”91 We are given more information on this game of skill when he expresses the need for training in the art of war, noting, “no one could become an adequate draughts or dice player who didn’t practice it from childhood on, but only gave it his spare time.”92 Book 4 names this game of skill when Socrates discusses how best to defend the city from attack: “Do you suppose any who hear that will choose to make war against solid, lean dogs rather than with the dogs against fat and tender sheep? … You are a happy one … if you suppose it is fit to call ‘[city-state]’ another than such as we have been equipping. … For each of them is very many [city-states] but not a [single city-state], as those who play say.”93 This quote was interpreted even in antiquity as a reference to the game City-State, where the primary operational logic was one of combination of one’s “dogs” into a single city-state and the fragmentation of one’s opponent’s rival city-state.94 Schädler identifies this reference to City-State and several references of Five Lines in the Laws as evidence that Plato was independently familiar with the rules and play of both games.95

For the following six books of the dialogue, City-State is continually alluded to as a model both of their city in speech and for their speeches themselves. When Socrates finally proposes his own definition of justice—that each citizen know their place and mind their conduct with others—he follows by expanding this to the just governance of one’s own soul: “A man calls his passions into check like a dog by a herdsman. This is just like the dogs who guard our city, who are put under the charge of the shepherds.”96 Justice is managing one’s passions like pieces in a game of strategy, in other words. The guardians tasked with protecting the city are repeatedly referred to as “dogs” throughout the dialogue, and Socrates continues to draw upon City-State as a model for how they should behave: “both when they are staying in the city and going out to war, they must guard and hunt together like dogs.”97 This method of strength in numbers was an important strategy in the game as well because isolated pieces were liable to capture when surrounded.

These ludic themes extend to Socrates’s description of the just city itself. The goal of legislation is not to benefit individuals but rather to “bring this [benefit] about in the city as a whole, harmonizing the citizens by persuasion and compulsion[,] not in order to let them turn whichever way each wants, but in order that it may use them in binding the city together.”98 The logic governing the just city is an extension of the operational logics of the game of City-State. The actions of each piece are motivated by a strategic necessity to combine with other pieces. Thus, this binding of the city together into a whole—the win condition of the game—is achieved through justice-as-combination. Likewise, a weak city is defined as one that “only needs a slight push to be divided into factions.”99 At the conclusion, Socrates returns yet again to City-State for his description of the role of the philosopher in responding to chance through reason: “One must accept the fall of the dice and settle one’s affairs accordingly—in whatever way argument (logos) declares would be best.”100 The rules and strategy of City-State contour the logics and central concerns of Plato’s city in speech.

But the most pervasive reference to the game occurs in the discussion of philosophical speech (logos) itself. In book 6, an interlocutor accuses Socrates of winning arguments through board-game maneuvers: “[B]ecause of inexperience at questioning and answering, they are at each question misled a little by the argument; and when the littles are collected at the end of the arguments, the slip turns out to be great and contrary to the first assertions. And just as those who aren’t clever at playing with draughts are finally checked by those who are and don’t know where to move, so they too are finally checked by this other kind of draughts, played not with counters but speeches.”101 This immobilization of game pieces by surrounding them matches what we know of the strategy of City-State and thus provides yet another piece of evidence that Plato used this precise game to model his own city-state. In addition, the analogy drawn between logos and game pieces can be extended to the philosopher’s city in speech (logos). This playful modeling activity might also be conducted with game pieces, which would help to explain the incessant swearing “by the dog” by Socrates and his interlocutors. It would also clarify many other veiled allusions throughout the dialogue: the references to hunting and encircling arguments, of Socrates “robbing” the others of “a whole part of their argument,” the “swarm” or “conspiracy” of arguments Socrates attempts to avoid, or his claim that the others “attack the argument at just the right place.”102 The rhetoric of the dialogue seems to present itself according to the operational logics of City-State.

The connection between board games and the verbal games of philosophy will become clearer in our discussion of the Laws. But we must also note that this is a through line of Plato’s dialogues. In the Gorgias, Plato has Socrates describe “other arts which work wholly through the medium of language (logos), and require either no action or very little, as, for example, the arts of arithmetic, of calculation, of geometry, and of playing draughts.”103 Here, in a further confirmation of the close relationship between board games and the mathematical arts, the movements of game counters and abacus counters alike are considered to be logoi. The description of philosophy itself as a game of words also appears in three of the pseudo-Platonic dialogues (Minos, Eryxias, and Hipparchus), and also indirectly in Aristotle’s On Sophistical Refutations.104 Thus, the comparison between game logics and philosophy was clear to Plato’s contemporaries and successors, too.

In both its association with language and with justice, the playable model City-State matches the earlier game of Passing. Both were embodied in the figure of Thoth—who was at once scribe, magical aide, and advocate for the deceased during their judgment. Thoth was strongly associated with Egyptian games, both by Plato and in extant inscriptions connected with Passing. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the game of Passing employed the operational logic of surrounding and displacing opponent pieces during one’s cosmic journey through the netherworld. When a deceased player defeated the god Mehen in their ritual game, Mehen declared the player ma’a cherou—justified—the same proclamation made by the god Anubis after the final judgment in the netherworld. In addition to bearing an etymological link to later Greek notions of cosmic judgment, the phrase evoked the Egyptian notion of judgment, Ma’at, which Susan Stephens and Bernal have both argued served as inspiration for Plato’s new description of justice.

Egyptian Ma’at thus helps to suture the concept of civic cohesion within a cosmic equilibrium, a formulation we find in the concluding chapter of the Republic. There, after Socrates tells his companions that one “must accept the fall of the dice and settle one’s affairs accordingly,” he describes life as a great contest (agon), “this contest that concerns becoming good or bad” for which the gods give the just victors “the greatest rewards and prizes.”105 This agon of justice he subsequently describes as a footrace—as in the Gorgias. But in the concluding myth where Socrates depicts the judgment of the deceased, it becomes clear that his concept of agonistic justice helps to maintain cosmic equilibrium. As he tells it, the eternal souls of the deceased await assignment to their new lives while standing before the goddess Necessity and her three daughters, the Fates. It is here that a spokesman casts lots in front of each soul, and afterwards, “he set the patterns of the lives on the ground before them.” Like the dice throw at the beginning of book ten that one must respond to with reason and calculation, the relationship between one’s lot and the pattern of one’s life completes the circle of Platonic justice, confirming once again an abiding relationship between the game model of the Republic and earlier Egyptian gaming traditions.

Strategies and Dialectics in Plato’s Laws

While the interlocutors in the Laws are also playing a game with logoi, it is evident from the start that they are playing a different kind of game. Rather than a mock trial where each of them attempts to surround and conquer the arguments of the other, the old men in the Laws are on a journey to a place at which they never arrive but which is analogized throughout with the soul’s journey after death. As they walk, the interlocutors are engaged in “playing at this moderate old man’s game concerning laws” because one of them has been tasked with planning the foundation of a colony in Crete.106 Once again, they determine to “construct a city in speech (logos)” to determine the necessary laws for regulating a just state—but they do so playfully, “like elderly children.”107 However, the emphasis by the anonymous “Athenian stranger” (said to be either Socrates or Plato) upon the necessity of good fortune for their project suggests this game has different operational logics than City-State.

Plato finally confirms the identity of this new game involving chance in book 5, when the Athenian stranger discusses the necessity of establishing sanctuaries at the center of one’s city before allotting other land: “The next move in the process of establishing laws is analogous to the move made by someone playing draughts, who abandons his ‘sacred line,’ and because it’s unexpected, it may seem amazing to the hearer at first. … But the most correct procedure is to state what the best regime is, and the second and the third, and after stating this to give the choice among them to whoever is to be in charge of founding in each case.”108 In this remarkable passage, the stranger makes a counterintuitive claim about the best course of action in founding cities—that because each lawmaker must respond to the fortunes that arise when planning their cities, it is important to design multiple possible cities and allow them to choose the best—and for his justification, he uses a strategy in the game of Five Lines—that of moving one’s piece from the protected holy line at the center in order to win a piece from one’s opponent. Moreover, the more foundational logic implied also coincides with the rules of Five Lines: each player must choose the most strategic piece to move based on their dice roll—an operational logic also present in Passing.

While the operational logic of combination in City-State became Plato’s model for justice in the Republic, the logic of exchange in Five Lines—which it likely borrowed from Passing—becomes a model for cosmos itself in the Laws. This becomes clear in a long description by the stranger in book 10 of a cosmic unity beyond that of the state:

“Now since the soul is always put together with the body, sometimes with one, sometimes with another, and undergoes all sorts of transformations caused by itself or by another soul, no other task is left for the draughts player except that of transferring the disposition that has become better to a better place, and the worse to the worse place, according to what befits each of them, so that it obtains the appropriate fate.…So all things that partake of soul are transformed, possessing within themselves the cause of the transformation, and, undergoing transformation, are moved according to the order and law of destiny: for smaller and lesser transformations of dispositions there is lateral regional movement; and when the transformations are greater and more unjust, there is a fall into the depths and the places said to be below … This, indeed, is the justice of the gods who hold Olympus.” 109

This sweeping passage—a clear reference to Heraclitus—describes the cosmic movements of souls according to the logics of a board game: the draughts player controlling the places of souls must plan for the fates of those souls by placing them correctly—sometimes displacing pieces with others depending on Fate’s dice roll. The logic of cosmic movement also accords with a game board; the lateral movements depict the soul’s quotidian progress through life, but truly unjust fates result in a game piece’s removal from the board itself. Five Lines, in its borrowings from Passing, is a game played by the gods. Indeed, central to pedagogy in the stranger’s new city of speech is an extensive description of Egyptian education, where arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy are taught through play—“draughts and these subjects of learning are not very widely separated from one another”—another man replies.110

As in the Republic, the operational logics of Five Lines also operate at the level of rhetoric. From the start, the old men declare the hope that their meandering journey is “accompanied by good fortune.”111 This theme of fortune as both a factor in lawmaking and of the narrative itself occurs throughout—such as when the men note how “fortunate” they were to “investigate what sort of chance it was that ever destroyed so great a system” of past city-states.112 They speak often of sequences of speeches, to use one “as a pattern for the others” and note at times how “the argument has come around again for the third or fourth time to the same thing.”113 These there-and-back logics are epitomized in book 3, where the stranger remarks that “we have come now once again, as if according to a god, to the point at the beginning of our dialogue about laws where we digressed and fell into topics of music and drunken carousals. … Now [that] we’ve gained this much by the meanderings of the argument …, we ought to discuss all these things again, from the beginning as it were.”114 We even see the operational logic of exchange detailed above hinted at earlier in the same chapter, helping to reinforce the association between punning references and games: “Lad, you are young,” says the Athenian, “and the passage of time will make you alter many of the opinions you now hold, and exchange them for their opposites. So wait until then to judge the greatest things.”115 The philosophers themselves and their speeches are game pieces moved along by the gods, sometimes progressing to their intended goal, sometimes being exchanged and displaced, and sometimes falling off the board entirely and starting the journey anew.

But their journey, as with the laws of the “city of words” they design, is still ultimately governed by chance. The dialogue concludes with the question of how to manage the risks of planning a city determined by fortune: “[I]f we’re willing to risk the entire regime and throw either three sixes, as they say, or three aces, then that’s what must be done; and I’ll share the risk with you.”116 Thus, the dialogue begins as it ends: with an invocation of fortune. This time, however, the men are not throwing the dice to determine the course of their arguments but the course of the city the arguments have formed. The dialogue brings the two together through its articulation of how laws are formed by a city, and like the evolution of justice in the Republic, the logic again conforms to ludic operations. In Plato’s rendering, expectations about the future are divided between “fears” and “boldness”—expectations of pain or pleasure. But for collectives, “over all these there is calculation as to which one of them is better and which worse—and when this calculation becomes the common opinion of the city, it is called law.”117 Laws emerge in a city-state when the collective learns to play the odds, when it calculates with logos the best response to bad rolls, when it weighs outcomes and plans contingencies. Plato’s laws, in other words, are strategies for the cosmic game of Five Lines.

While a complete lack of textual evidence concerning the Egyptian game of three by eleven prevents establishing any parallels between its play and that of Five Lines, the entanglement of both games within broader metagaming practices can help us tease out symbolic relationships that figure centrally in Plato’s Laws. Plato’s repeated emphasis on calculation is one instance, and it reminds us that Five Lines boards were widely used as abaci—an association Plato also extends to Egyptian board games. Furthermore, an inscription on a New Kingdom game of Four Rooms dedicated to the “real scribe of calculations, who is not unreliable” hints at the possibility that this precursor to the three-by-eleven game also had an association with abaci.118 The much greater emphasis on the role of chance in Laws compared with the Republic is another example of the difference between the affordances of City-State and Five Lines as models. The ubiquitous connection between Five Lines boards and cubic dice originating in Southwest Asia both reinforces the cosmic symbolism of the game and reminds us that its operational logics were much more dependent on uncertainty than those of City-State. The narrative of a cosmic journey mediated by chance elements and corrected only through successful strategy was the defining element of Passing from its first entanglement with Mehen and Endurance in the Middle Kingdom and for the remainder of its history. In both their form and their content, Plato’s Republic and Laws bear the discursive traces of a material history of gaming practices beginning in Egypt and spanning the Mediterranean.

Changing History Now

An understanding of games as flexible collections of operational logics and models fitted to specific purposes by communities of metagamers has profound implications for the sorts of histories we can tell about games. Rather than assuming by default that games are insular formalisms with arbitrary and rigid rule sets, perhaps histories of games can begin with the assumption of the many rich connections among various games and amid other ways of knowing and doing. This more capacious vision of game histories will likely change our understanding of what games have been about. But it also enlists game historians in the more uncertain task of discovering what other structures and logics were also about games.119

If Greek philosophy was substantially influenced in both its content and its form by gaming practices originating in Egypt, as I have argued, then the history of games can no longer concern itself primarily with objects, practices, consoles, and platforms that pass themselves off as games in our moment. Instead, our role as historians must include the outcomes of these playable models as well—the concepts veering in and out of discourse, giving themselves new backstories and covering their tracks. I am suggesting that historians of games address themselves to the ludic production of practices through an attention to the material negotiations of game forms by communities of metagamers and the production of concepts out of the ludic stuff called operational logics. This proposal has a politics: that the solid things of our moment be treated as the products of playthings. But it also has a promise: that through so doing we can reroll the present.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux, both of whom provided invaluable feedback and formative suggestions. This article would not exist without their help. I would also like to thank Julia Puglisi and Christian Casey for their generosity and for providing resources during my early foray into Egyptology. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the hard work of the ROMchip editors and my anonymous reviewers, whose careful reading and comments helped me to better express my claims.

Footnotes

1. ^ In this article, I use philosophy to refer to a specific tradition of thought consciously based on the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and others in the school of philosophy in ancient Greece. I am by no means suggesting that this tradition of thinking ought to be privileged over any other.

2. ^ Recent work articulating the use of games as models includes: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, How Pac-Man Eats (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020); Patrick Jagoda, Experimental Games: Critique, Play, and Design in the Age of Gamification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020); Alenda Y. Chang, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019); Claus Pias, Computer Game Worlds, trans Valentine A. Pakis (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2017); and Colin Milburn, Mondo Nano: Fun and Games in the World of Digital Matter (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

3. ^ Quoted in Phiroze Vasunia, The Gift of the Nile: Hellenizing Egypt from Aeschylus to Alexander (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 10.

4. ^ Martin Bernal, Black Athena Writes Back: Martin Bernal Responds to His Critics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 366–67.

5. ^ James McEvoy, “Plato and the Wisdom of Egypt,” Irish Philosophical Journal 1, no. 2 (Autumn 1984). For a survey of Egyptian influences on early Greece, see Ian Rutherford, ed., Graeco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BCE–300 CE (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

6. ^ Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, vol. 1, The Fabrication of Ancient Greece, 1785–1985 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020).

7. ^ Quoted in Robert Hahn, Anaximander and the Architects: The Contributions of Egyptian and Greek Architectural Technologies to the Origins of Greek Philosophy (Albany: SUNY Press, 2001), 18. Hahn also gives a thorough and incisive account of this mentality and its limitations (15–38).

8. ^ See, for instance, discussion in Molly Myerowitz Levine, “Review Article: The Marginalization of Martin Bernal,” Classical Philology 93, no. 4 (October 1998): 345–63.

9. ^ Further discussed below. Emily Vermeule, Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981); and Sarah P. Morris and John K. Papadopoulos, “Of Granaries and Games: Egyptian Stowaways in an Athenian Chest,” Hesperia Supplements 33 (2004): 225–42.

10. ^ Bernal, Black Athena Writes Back, 345–70.

11. ^ Leslie Kurke, Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold: The Politics of Meaning in Archaic Greece (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 247–98.

12. ^ Reviel Netz, “Counter Culture: Towards a History of Greek Numeracy,” History of Science 40, no. 3 (2002): 321–52. See also Véronique Dasen and Jérôme Gavin, “Game Board or Abacus? Greek Counter Culture Revisited,” Board Game Studies Journal 16, no. 1 (2022): 251–307.

13. ^ Walter Crist, “Debunking the Diffusion of Senet,” Board Game Studies Journal 15, no. 1 (2021): 13–27; and Helène Whittaker, “Board Games and Funerary Symbolism in Greek and Roman Contexts,” Myth and Symbol 2 (2004): 279–302.

14. ^ Mia Consalvo and Christopher A. Paul, Real Games: What’s Legitimate and What’s Not in Contemporary Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

15. ^ For example, see T. L. Taylor, Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012). Some historians of board games are also taking important steps to reframe this debate. For instance, Barbara Carè, Véronique Dasen, and Ulrich Schädler, “Back to the Game: Reframing Play and Games in Context—An Introduction,” Board Game Studies Journal 16, no. 1 (2022): 1–7.

16. ^ Wardrip-Fruin, How Pac-Man Eats, 10.

17. ^ Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux, Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 17.

18. ^ Boluk and LeMieux, Metagaming, 25.

19. ^ See discussion in Max Nelson, “Battling on Boards: The Ancient Greek War Games of Ship-Battle (Naumachia) and City-State (Polis),” Mouseion 17, no. 1 (2020): 3–42.

20. ^ Nelson, “Battling on Boards,” 36.

21. ^ Kurke, Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold, 247–98.

22. ^ Despina Ignatiadou, “Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite,” Archimède: Archéologie et Histoire Ancienne 6 (2019): 144–59.

23. ^ Ulrich Schädler, “Greeks, Etruscans, and Celts at Play,” Archimède: Archéologie et Histoire Ancienne 6 (2019): 160–74.

24. ^ Ulrich Schädler, J. Retschitzki, and R. Haddad-Zubel, “The Talmud, Firdausi, and the Greek Game ‘City,’” in Step by Step: Proceedings of the 4th Colloquium Board Games in Academia (Fribourg: Editions Universitaires, 2002); and Stephen Kidd, “Pente Grammai and the ‘Holy Line,’” Board Game Studies Journal 11, no. 1 (2017): 83–99.

25. ^ Nelson, “Battling on Boards,” 4.

26. ^ Niklas Hillbom and Walter Crist are cautious about making links between Greek games and earlier gaming practices in Minoan Crete and Cyprus, respectively, due to the paucity of evidence that these earlier games continued to be played in the Archaic period. Nevertheless, it is worth considering the possibility that the Egyptian Endurance enjoyed a similar popularity to Mehen on these islands long after its use ceased in Egypt—perhaps as the game of “ten-ring” or “twelve-ring” discussed by Nelson. Nelson, “Battling on Boards,” 8.

27. ^ Siegfried Laser, Sport und Spiel (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987).

28. ^ Piccione and others have argued convincingly that Passing was already being played in the First Dynasty. I also consider below the suggestion that a version of the game was in use in the Predynastic period (fourth millennium BCE). Peter Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet and Its Significance for Egyptian Religion” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1990). See also, Edgar B. Pusch, “Das Senet-Brettspiel im Alten Ägypten/T. 1. Das Inschriftliche und Archäologische Material T. 1 Textband,” Das Senet-Brettspiel im Alten Ägypten 38 (1979): 156–57.

29. ^ For a series of reconstructions of the rules of Passing, see “Senet (Znt),” Ludii Portal: Home of the Ludii General Game System, https://ludii.games/details.php?keyword=Senet.

30. ^ Piccione, “Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 27 (1990): 43–52.

31. ^ Peter Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet,” 96–154.

32. ^ Piccione, 96–154.

33. ^ See discussion in Timothy Kendall, “Mehen: The Ancient Egyptian Game of the Serpent,” in Ancient Board Games in Perspective: Papers from the 1990 British Museum Colloquium with Additional Contributions, ed. Irving L. Finkel (London: British Museum Press, 2007).

34. ^ Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet.”

35. ^ Walter Crist, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi, and Alex de Voogt, Ancient Egyptians at Play: Board Games across Borders (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 37–38. The authors in this study describe the board as having eight lines. In my own visual inspection, I identified a ninth faded line at the top of the board, making the spaces between each line roughly equidistant.

36. ^ As cataloged in Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet.”

37. ^ Pusch, “Das Senet-Brettspiel,” 156–57; and Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet.”

38. ^ Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet,” 121–24, 164.

39. ^ Benedikt Rothöhler, “Mehen, God of the Boardgames,” Board Games Studies 2 (1999): 10–23.

40. ^ Rothöhler, “Mehen,” 18–20.

41. ^ John Z. Wee, “Five Birds, Twelve Rooms, and the Seleucid Game of Twenty Squares,” Mesopotamian Medicine and Magic: Studies in Honor of Markham J. Geller, ed. Strahil V. Panayotov and Ludêk Vacín (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 833–76; and Crist, Dunn-Vaturi, and de Voogt, Ancient Egyptians at Play, 144.

42. ^ Crist, Dunn-Vaturi, and de Voogt, Ancient Egyptians at Play, 138–42.

43. ^ Crist, Dunn-Vaturi, and de Voogt, 168–69.

44. ^ Edgar B. Pusch, “The Egyptian ‘Game of Twenty Squares’: Is It Related to ‘Marbles’ and the Game of the Snake,” in Finkel, Ancient Board Games in Perspective, 69–86.

45. ^ Plato, Phaedrus, Loeb Classical Library 36, trans. H. N. Fowler (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), 274c–d.

46. ^ Christoph Poetsch, “Das Thothbuch: Eine Ägyptische Vorlage der Platonischen Schriftkritik im Phaidros?,” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 103, no. 2 (2021): 192–220.

47. ^ Piccione, “The Historical Development of the Game of Senet,” 343, quoting and translating Bernard P. Grenfell, The Oxyrhynchus Papyrus, vol. 3 (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1898), 141–43.

48. ^ Compare María Antonia García Martínez, “Astronomical Function of the 59-Hole Boards in the Lunar-Solar Synchronism,” Aula Orientalis 32, no. 2 (2014): 265–82.

49. ^ Translation from “Gorgias of Leontîni: Fragments,” Demonax: Hellenic Library Beta, http://demonax.info/doku.php?id=text:gorgias_fragments.

50. ^ Deborah Tarn Steiner notes a profoundly ambivalent posture toward the foreign invention of writing shared by many authors writing in Greek. Deborah Tarn Steiner, The Tyrant’s Writ: Myths and Images of Writing in Ancient Greece (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

51. ^ Richard Claverhouse Jebb, ed., Sophocles: The Plays and Fragments, vol. 2 (University Press, 1889), fr. 479. See Nelson, “Battling on Boards,” 129n32, for a list of sources attributing game technologies to Palamedes.

52. ^ Aeschylus, “Suppliant Women,” Aeschylus, vol. 2, trans. Herbert Weir Smyth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926), lines 11–15.

53. ^ Geoffrey Bakewell, “Aeschylus’ Supplices 11–12: Danaus as ΠΕΣΣΟΝΟΜΩΝ,” Classical Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2008): 303–7.

54. ^ Descriptions of the movement toward sanctuary mediated by fortune are also highly evocative of Five Lines. See Aeschylus, “Suppliant Women,” esp. lines 82–90, 176–206, 605–24, and 935–96.

55. ^ Christopher S. Dobbs, “Not Just Fun and Games: Exploring Ludic Elements in Greek and Latin Literature” (PhD diss., University of Missouri Columbia, 2018), 70–72.

56. ^ See Kurke, Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold.

57. ^ Ignatiadou, “Luxury Board Games.”

58. ^ Nelson “Battling on Boards.”

59. ^ Alex de Voogt, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi, and Jelmer W. Eerkens, “Cultural Transmission in the Ancient Near East: Twenty Squares and Fifty-Eight Holes,” Journal of Archaeological Science 40, no. 4 (2013): 1715–30.

60. ^ Walter Crist, “Games of Thrones: Senet as Social Lubricant in the Ancient Near East” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2016), 284.

61. ^ This pattern of signs on every third row evinces an early relationship to the game Four Rooms, which almost always included a sign—often a rosette—on every fourth row of the twelve central cells. It also comports with “Hounds and Jackals” boards, which bore a distinctive mark on every fifth row. Interestingly, “Hounds and Jackals” was often depicted with two rows of either ten or eleven holes in the middle track. Kendall has even gone so far as to suggest Endurance was reconfigured as “Hounds and Jackals,” although the nature of this relationship is unsubstantiated. See Pusch, “The Egyptian ‘Game of Twenty Squares’”; and Timothy Kendall, “Mehen: The Ancient Egyptian Game of the Serpent,” in Finkel, Ancient Board Games in Perspective, 33–45.